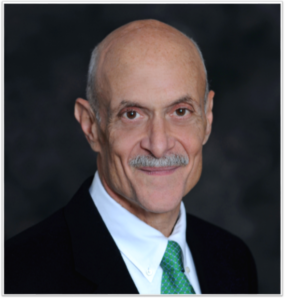

On May 27, inFOCUS editor Matthew RJ Brodsky interviewed Michael Chertoff, the secretary of the Department of Homeland Security from 2005-2009. As secretary he developed and implemented border security policy, homeland security regulations, and a national cyber security strategy. He also served periodically on the National Security Council and the Homeland Security Council, and on the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States. Prior to his appointment to the Cabinet, Mr. Chertoff served as the assistant attorney general for the Criminal Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, where he oversaw the investigation of the 9/11 attacks. Today, he is senior of counsel at the law firm of Covington & Burling in Washington, DC.

iF: The Obama administration decided to abandon the term “war on terror” in favor of “overseas contingency operation.” Is this a semantic shift, or does it have practical consequences?

MC: Actually, I don’t know if that’s accurate. I don’t know that they have abandoned it. Sometimes I hear them use it and sometimes I hear them not using it, so I don’t want to characterize what their position is.

I think that the problem with the war on terror is that it is treating terror as a tactic. Although I think we all know what we mean when we say it, but I mean if you want to be literal it’s not literally accurate because terror is a tactic. I think that we are at war. I do think that the enemy is radical Islamist ideologues and their network. Obviously, al-Qaeda is part of that network but there are other parts of that network as well. And, we are in different degrees of war. We are in a hot war with some and a cold war with others. So it’s a little more complicated than the sound-bite but I think it is more accurate.

iF: Just yesterday the president’s top counterterrorism advisor, John Brennan, described the violent extremists as victims of political and economic social forces. But he said that those plotting attacks in the U.S. should not be described in religious terms. So if America’s adversaries are very clear in how they define us as enemies, why is it so difficult for the U.S. to identify with whom we are at war? Is the administration currently missing the boat here?

MC: Well again, I spent a lot of time when I was secretary talking to people, including many Muslims, about what is the right way to refer to adherents to the ideology that we’re fighting. And, there is an Arabic term, takfirism, which means basically the view is that everybody who disagrees with me is an apostate and should be killed, which is probably the most accurate but unintelligible. I don’t think you can avoid the fact that the people in this ideology are arguing, incorrectly, but nevertheless arguing, that they are reflecting a religious mandate. And so what I like about the term “radical Islamism” or “extremist Islamism” is that it makes it clear that we’re talking about Islam not as a religion but as a political doctrine – and that we’re talking not about all political Islam but extremist political Islam.

That being said, if we are not willing to be candid about the fact that it is a self-described movement that claims religious roots, then we’re not being honest about what it is we’re facing. Similarly, when I was a prosecutor, we did organized crime. I’ll never forget Governor Cuomo criticized us for using the term “La Cosa Nostra mafia.” Then I was the U.S. attorney prosecuting a case called the “Commission Case,” and we had tapes where the guys on the tapes said: “we’re the mafia, we’re La Cosa Nostra.” And so when the tapes got played in court, Cuomo got embarrassed. And Rudy [Giuliani] was Italian. But nevertheless he acknowledged that the group itself, while not emblematic of Italians by any means, did select only Italians or people of Italian lineage to be made members, and that was a self-imposed rule. So you can’t ignore that; that was part of how the group set itself up. So, to me, radical Islamism or extreme Islamism is probably the right balance to have.

iF: Do you see a pattern in the recent spate of terrorist incidents at Fort Hood, the Christmas Day bomber and Times Square. What do these mean?

MC: Well, we’ve had homegrown terrorists before. If you go back to 2002-2003, the Lackawanna Six – the people that we convicted up in Oregon and Washington. It does seem like there’s an uptick. And I think it’s attributable to two reasons. First, there’s been a self-conscious effort on the part of the extremists to recruit Americans or lawful residents because its gotten much harder to bring foreigners into the country. And second, I think that there’s been a tendency for some populations that have been alienated in this country to become a little bit more active. I think we’ve got much less of that than the Europeans have, by a considerable measure. But we’re a large country and you’re going to find some people who are alienated, and this ideology is one attractive way for them to deal with their alienation.

iF: In January the Pentagon released its report on the Fort Hood massacre carried out by Major Nidal Hasan. Defense Department Secretary Gates said there were “shortcomings” in the Department’s ability to defend against internal influences. In his speech after the failed Christmas Day bombing, President Obama said there were “systematic failures.” Janet Napolitano said, “the system worked.” Which is it? What is the state of our counterterrorism capabilities?

MC: I think our counterterrorism capabilities are good and they’re very much better than they were prior to September 11. They are not perfect, and I think in some cases what you see is human error – people who just didn’t see something they should have seen or perhaps didn’t work as urgently as they should have worked. And that’s what my focus would be. You need to drive this as a matter of leadership; it’s got to be a front-burner issue. The second piece is that you need to continually adapt. The tactics and strategies that worked last year are not all going to work this year because the enemy has adapted. So there’s a need for continuous improvement and focus. And you also finally have to support your field operatives. You know, the people you’re sending out in the field – you’ve got to have their back.

iF: Are we doing that?

MC: Well, I think the decision to go back and revisit the issue of prosecuting CIA agents after that was previously declined was probably not a helpful message. Right now, according to the newspapers, we’re using armed force against people in Pakistan and Yemen. So assuming that to be true, I hope and I would expect that we have the backs of the people who are doing that and in a year or two somebody’s not going to come back and say: “Whoa, wait a second. This is murder and we’ve got to investigate that.” To me, it’s leadership, it’s adaptation, and it is supporting your troops. Those are the three pillars of staying ahead of this.

iF: Did the decision to quickly pivot to charging the Christmas Day bomber as a criminal interfere with investigators’ ability to obtain the maximum amount of information? Was it the right decision?

MC: I can’t answer that because I wasn’t in the room. I think what they did with the Times Square bomber shows a more deliberate and thoughtful approach. Now, sometimes the answer may be that you give a person his Miranda rights because you’ve exhausted everything you can get out of him and, you know, in some of the cases we had we had been investigating people for months. So we had wiretaps and stuff, so we knew everything. The point is that it’s got to be a thoughtful decision; it can’t be a reflex to automatically default to the criminal justice system.

iF: The attempted car bombing in New York on May 1 has been traced back to a Pakistani-born U.S. citizen who spent five months in Pakistan last year. The Tehrik e Taliban Pakistan has claimed responsibility for the attack. What do you make of the fact that nearly every attempted or successful terror attack on Western targets in recent years has been traced back to Pakistan in some capacity?

MC: Well, the Christmas Day would-be bomber was Nigerian who went to Yemen. And we’ve had cases of Somalians. I think that Pakistan is probably still the epicenter of where this extremism is planning and training. But I think we have to watch Somalia, we have to watch Yemen, and we even have to start watching North Africa. I was in North Africa about a week ago and there’s a growing concern there about al-Qaeda in the Maghreb, which is involved in drug trafficking and kidnapping. That group could become the next Yemen. So this is a spreading problem; this is not limited to one geographic area.

iF: The United States has been using unmanned aerial drones to target al-Qaeda and Taliban leaders in Pakistan’s lawless tribal areas. Some have questioned the legality of these “targeted assassinations” while the Obama administration has insisted they are lawful acts of war done in conjunction with the Pakistani government. What is your take?

MC: Well, assuming this to be true, what’s reported, I’m not going to confirm anything, but assuming that to be true I don’t have a problem legally with using force when you’re at war. But some people on the left have not at least hitherto accepted that we are at war, so they’re going to have to figure out how they deal with this issue. I don’t have a problem with it.

iF: Attorney General Eric Holder has been widely criticized, first for deciding to try terrorist mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed in civilian court in New York City, and then for reversing his decision earlier this year. What do you think is the appropriate venue for trying terrorism suspects – civilian court or military tribunal?

MC: I think for people who are captured oversees, I would put them in a military commission. Unless they’re American citizens who under the current law are not allowed to be in a military commission. But if you’re not an American and you’re captured oversees, I see no reason to import you to the United States. Now, people captured in the United States present a different set of issues…

iF: Even if they’re foreign-born?

MC: Even if they’re foreign-born presents a different set of issues. But, certainly if you’re captured oversees I think it’s the right course to put them in a military commission. And frankly I don’t think you need to bring them into the U.S. to do that. I think you can try them somewhere else.

iF: What do you make of the decision to close Guantanamo Bay?

MC: I think it’s going to turn out to be a lot harder than was originally projected. Part of the problem is this: In a way, the easiest way to deal with it is that if someone’s been convicted and they’ve gotten life imprisonment or execution, that’s the easiest thing. You could then put them in a U.S. facility; lock them up at a place like Florence and that would be that.

The people who have not been tried yet or who are being detained, that’s the hard problem because what do you do if at the end of the day you can’t make a criminal case under U.S. criminal law? Do you release them in the U.S.? Do you deport them? Well, look what just happened in Great Britain. A week ago an immigration court in Britain said we have two terrorists that were acquitted, or there was insufficient evidence to charge them with a terror plot. But the court said: these are terrorists. One is clearly a member of al-Qaeda and the other is clearly ready to carry out al-Qaeda’s orders. But, under European law, because there is a slight risk they can be mistreated back in Pakistan, we’re not going to send them back but they have to remain in Great Britain. Now what? Are they going to put them under these control orders? That’s controversial, too. Well, we don’t want to have that in the United States. I can guarantee you that would be a huge mistake. So, before you start bringing people from Guantanamo into the United States you better have all the legal ducks in a row as to what happens if people can’t be convicted. And I don’t think we’re there yet.

iF: What do you make of the report of the transfer of Scud missiles from Syria to Lebanon-based Hezbollah? Is this a “game-changer,” as the Israeli’s have insisted? How should the U.S. respond and does Hezbollah present a threat to the United States or American interests?

MC: Without commenting on the specific report, I think Hezbollah, as I think I’ve said publicly before, is in terms of sophistication the most powerful of the terrorist groups. I mean, they are much more sophisticated than al-Qaeda. They have not attacked Americans directly to my knowledge since the Khobar Tower in 1996. But they do have a growing presence in this hemisphere, which they’ve been in the process of gaining over a period of decades now. I think that the issue has always been: at what point would they engage in hostilities with the United States? I think a lot of that is frankly tied to where we are with Iran. So I think they’re a piece of a larger geo-political issue having to do with Iran and its relationship with the United States and its relationship with the other countries in the region.

iF: Some have argued that the creation of the Homeland Security department merely adds one more level of bureaucracy and red tape to the government. How essential is the department to keeping the U.S. safe? Does it help or hinder the flow of information between governmental agencies?

MC: Actually, it made it much easier. We used to have the various pockets of things that were involved with border and infrastructure security scattered in different departments. So you had a piece of the border stuff in the Department of Justice, another piece in Treasury, another piece in the Department of Transportation, and they never worked together. They had uncoordinated plans. By bringing this department together, we for the first time built a coordinated border plan, which is one of the reasons that – contrary to what you hear on the news – we’ve actually had significant decreases in flow across the border in the last couple of years. We now share platforms between the Coast Guard and Customs and Border Protection. They share intelligence, they have joint planning, and they have joint exercises. So I think like any other maturing organization there are some growing pains, but I think it is significantly far ahead in terms of coordinating on border and infrastructure security than was the case when they were in separate departments.

iF: Excellent. Thank you very much for your time.