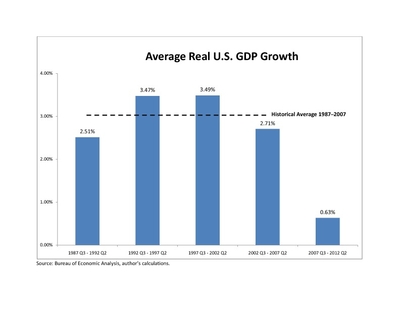

The engine of growth that has fueled the U.S. economy for over 225 years appears idle. In the five-year period from the second half of 2007 through the first half of 2012, the U.S. GDP growth rate has averaged just 0.6 percent annually. In fact, as the accompanying chart indicates, the average annual growth rate of the U.S. economy has been below 1 percent during the last five years, far slower than its recent historical average.

The engine of growth that has fueled the U.S. economy for over 225 years appears idle. In the five-year period from the second half of 2007 through the first half of 2012, the U.S. GDP growth rate has averaged just 0.6 percent annually. In fact, as the accompanying chart indicates, the average annual growth rate of the U.S. economy has been below 1 percent during the last five years, far slower than its recent historical average.

Furthermore, a recent report by the U.S. Census Bureau indicates that the median household income in the United States in 2011 declined for the second consecutive year to $50,054. On an inflation-adjusted basis, the median household income in 2011 was 8.1 percent lower than in 2007. And finally, the average unemployment rate in the first nine months of 2012 has been 8.2 percent. While an improvement relative to 2010 and 2011, the labor market remains weak as 12 million workers are unemployed.

America cannot move forward without a comprehensive strategy to reignite the engine of growth and return the U.S. economy to historical growth rates—or beyond. In the absence of real economic growth, America will face unending fiscal debt burdens, many workers will remain or become discouraged or unemployed, and the nation will eventually fall behind other countries that have embraced growth-oriented policies.

There is no single domestic policy reform that will achieve this goal of economic rebirth. Only a comprehensive, multi-pronged strategy will lead to a fiscal framework that encourages the investment in human and physical capital and educational and physical infrastructure necessary for the economy to grow. Three components in particular are critical for setting a successful growth agenda: reforming the tax code, facilitating free trade, and reforming entitlement programs.

Consequences of a Weak Economy

The consequences of the United States’ poor economic performance are far-reaching. While 8 percent unemployment is bad news, the situation among many subpopulations is actually much worse. The unemployment rate among those with less than a high school diploma was 12 percent in August 2012 while those with a bachelor’s degree or higher faced an unemployment rate of just 4.1 percent. The unemployment rate varies geographically as well. Workers in California, Rhode Island, and Nevada have all experienced unemployment rates above 10 percent over the last 12 months.

The sustained weak labor market has left over 5 million workers in long-term unemployment, defined as 27 weeks or more. The consequences of the prolonged weak economy are particularly damaging for these workers, as their ability to reenter the workforce declines. Furthermore, sustained unemployment severely strains household finances and has been shown to lead to worse health outcomes, both physically and psychologically.

The slow rate of economic growth and the decline in household income may have broader economic implications as well. Investment flows into economies with healthy expected growth rates. The dismal performance of the U.S. economy may lead capital to flow into other markets. And a sustained weak economy may discourage workers from making investments in themselves through training or higher education if there is not a reasonable expectation that they will earn higher wages as a result.

There are also critically important fiscal policy consequences of sustained weak economic growth. The federal government is completing its fourth consecutive year with a federal deficit in excess of $1 trillion. And the publicly held debt as a share of GDP has doubled in the last five years from 36 percent of GDP to 73 percent.

Tax Reform

Tax reform is a crucial element to getting the U.S. economy back on track. The current tax system—dominated by the individual income tax—inhibits economic growth. By taxing the returns to savings, the income tax encourages consumption over investment, to the detriment of long-term economic growth since investment is a greater driver of economic growth than consumption. As this author explains along with Alan Viard in the recent book, The Real Tax Burden: More Than Dollars and Cents:

An economy can increase its output over time only by using better technology to turn inputs into output or by increasing its inputs. One of the primary inputs used in production is capital, such as plant and equipment, which is financed by saving. Without saving to finance the building of plant and equipment, long-run economic growth is greatly diminished. A common misconception holds that consumption, rather than saving, is good for the economy because consumer spending creates jobs. This misconception confuses short-term economic fluctuations in performance (or underperformance) of the economy with long-run growth.

In addition to the penalty on saving, distortions in the tax code in the form of credits, deductions, and exclusions make the tax code inefficient, requiring higher individual income tax rates than would be necessary to bring in the same amount of revenue in the absence of tax preferences. Eliminating or curbing the worst of these “tax expenditures” would promote economic growth.

Depending on the precise reform and the assumptions of the macroeconomic model employed, growth estimates are quite large. Alan Viard, in his recent book, Progressive Consumption Taxation: The X Tax Revisited, estimates 5 percent growth from moving to a consumption tax from an income tax system. Kevin Hassett and Alan Auerbach, in a book they co-edited titled Toward Fundamental Tax Reform, estimate 5–10 percent growth from tax reform.

The political pressures Congress would face in attempting tax reform could unfortunately lead to less than theoretically optimal reform. Regardless of this, there are many strong reasons to pursue changes in tax policy. Difficult political terrain must be tread carefully, but it should not be taken as a deterrent to pursuing reform that is in the public interest and will spur economic growth. Beyond matters of fairness and simplification for tax payers, tax reform could boost the economy considerably.

Trade Liberalization

Broader trade liberalization offers great economic growth potential. Yet, tremendous distortions and barriers to trade remain. The consequences of these are both economic and geopolitical. As the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) concluded after examining the potential benefit from liberalization of only world agricultural trade:

The United States and, to a lesser extent, its agricultural sector would benefit economically from reductions in agricultural tariffs and subsidies worldwide. Many other countries, including all major developed countries and most developing countries, would also see a net economic benefit. . . . Roughly 80 percent to 90 percent of the benefit from liberalization would come from eliminating tariffs and similar import restrictions.

Bilateral and multilateral free trade agreements also offer a way to promote economic growth through trade. The United States enacted eight free-trade agreements (FTAs) between 2001 and 2006. Last year, Congress passed three more. While most of these agreements have been small, they represent at least incremental progress toward greater trade liberalization. However, it will now be much more difficult to establish new FTAs given the expiration of a key means of facilitating these agreements: Trade Promotion Authority. This process allowed for the fast tracking of FTAs and is a vitally important legislative tool for reducing trade barriers, promoting exports, and encouraging growth. Only if Congress and the Executive Branch seek reenactment of the Trade Promotion Authority and then pursue an aggressive campaign for free trade will consumers and exporters alike be able to realize the gains from more trade.

Entitlement Reform

An integral part of any comprehensive economic growth agenda for America must include significant reforms to entitlement programs. The projected spending forecasts for Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security pose a threat to the federal government’s ability to meet its other obligations. Moreover, these programs actually can discourage individuals from working and saving.

For example, the availability of Medicare benefits when an individual reaches the age of 65 discourages that worker from continuing in the workforce even if he or she is able. Aligning the Medicare eligibility age with the normal Social Security retirement age, which is currently being phased up to 67, would reduce Medicare spending by 5 percent, according to Maya MacGuineas of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

Beyond helping the budget, changes to the eligibility age for Medicare and the early eligibility age (EEA) for Social Security, currently at 62 years, would grow the workforce and thus the economy. Fellow American Enterprise Institute economist Andrew Biggs has estimated that raising the EEA to 65 could increase GDP by 5.5 percent in the long run. CBO has confirmed that such a policy would benefit the long-run economy. They estimate that raising the EEA two years to 64 would induce workers to remain in the workforce for an additional 8 months on average. According to CBO, raising the Medicare eligibility age to 67, the Social Security EEA to 64, and the Social Security full-retirement age to 70 would, taken together, increase the size of the economy by about 3 percent in the long run.

In addition, there are several incremental reforms that could be made to Social Security that would go a long way toward restoring the program to sustainability. These include modifying the benefit formula to slow future benefit growth and adopting a more accurate method for calculating the annual cost of living adjustment. Reductions in benefits these reforms would bring about would not be politically easy to implement. But some tightening of the belt is essential, and policymakers have the thankless task of being in charge of introducing some fiscal austerity. To make the changes as gentle as possible for Social Security beneficiaries, these two reforms would at least minimize distress by limiting benefit growth gradually and not cutting benefits outright.

Moving the U.S. Economy Forward

It is of critical importance that Washington makes economic growth a core component of putting America’s fiscal house in order. In large part, moving America forward means moving the U.S. economy forward. For the United States to be strong on the global stage, it must restore fiscal sanity and return—at least—to historical levels of economic growth. While there is no single policy that will reignite the economy, the measures outlined above for tax reform, trade liberalization, and entitlement reform offer a way to invigorate the stagnant economy and address entitlement challenges before they get even worse. Ultimately, even more must be done. Education reform, a robust and rational national infrastructure, and a coherent energy policy all must be pursued to ensure that America’s workers and employers are well suited to the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century global economy.

Alex Brill is a research fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, DC. Previously, he was chief economist and policy director to the House Ways and Means Committee.