Hundreds of armed men stormed a polling office in Benghazi Monday as Libya gears up to vote for parliamentary elections scheduled for July 7. Though Muammar Qaddafi was overthrown last year, the country remains in turmoil as tensions grow between various political parties and armed tribes. Many Libyans worry that the Transitional Council cannot guarantee their security during elections. Others note that growing calls for boycotting the elections amongst Libya’s tribes could possibly tarnish the already shaky transition process.

These developments come after two militant attacks last month; a bomb targeting America’s consulate in Libya and the seizure of Tripoli’s airport by armed tribesmen in a bid to force Libya’s government to explain the whereabouts of the group’s leader, Abu Ajila al-Habshi. The two events were unconnected, but they highlight the Libyan government’s inability to manage the country as local grievances grow out of control.

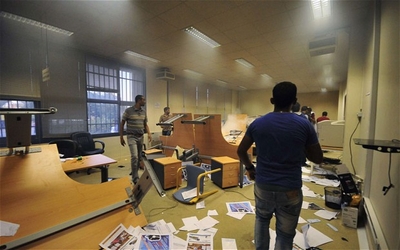

Protesters storm the office of the national election commission in Benghazi. (Photo: Reuters) |

While the country itself is fragmented along tribal lines, Islamism seems to be gaining ground. Some Islamists, such as Sufian Bin Qumu, argue that they will refuse to turn over weapons until a Taliban-like government is established in Tripoli. While most in the country remain moderate, extremists’ growing role in Libya has many worried about the region’s stability. According to Army Gen. Carter F. Ham of the U.S. Africa command, “… we see some worrying indicators that al-Qaida and others are seeking to establish a presence in Libya.”

Libya’s transitional government has even resorted to the former regime’s security apparatus in recent months in an effort to stabilize the country and stymie a pro-Qaddafi counter-revolution. Commander of the Tripoli branch office of Preventative Security, Adel al-Morsi, noted that “The revolution must use all means necessary to rid the country of enemies” if it hopes to survive, leading some activists to question the government’s commitment to reform. The eastern tribes’ suspicion that the central government is tied to tribes in western Libya doesn’t help matters.

While the majority of the country seems willing to participate in a democratic system and eschews violence, the government’s deteriorating hold on central power, tribal squabbles, and growing extremism undermine any transitional election. Libya will not magically stabilize after the elections. The road ahead for the country seems long indeed.