The Middle East has been both a laboratory for and cauldron of contemporary war for more than a generation. But in the last generation (i.e. since Operation Desert Storm in 1990-91), the greater Middle East including Afghanistan has been the epicenter of contemporary warfare and, until Ukraine, seemingly the place where the characteristics of modern warfare were on full display. The scope of the humanitarian disasters these wars have caused is now the stuff of daily journalism and represents the greatest humanitarian crisis of our time. In this respect they point first to the failure of governments in the Middle East to obtain legitimacy and provide security, and second to the centrality of the role of governments in any study of the wars of our time there.

This centrality of the political factor is critical since for twenty-five years America has waged a series of wars in the Middle East to promote better governance—if not actual democracy—and has lost every war since 2000 that it has fought there. Thus we cannot escape the brutal fact that for a generation, since Desert Storm, U.S. policy in the Middle East has been and continues to be afflict-ed with a high degree of strategic incompetence that is arguably quite rare in the annals of history. This failing has been and continues to be a bipartisan affair, not the monopoly of any party or branch of the U.S government. A major cause of this failure in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria is the fact that the U.S. (and its allies) have never had any conception of strategy or an adequate strategy for bringing these wars to a conclusion that could be defined as victory. Analysts and commentators here and abroad, including the Russian government, have all pointed to this fact and warned about the consequences of this failure. And while we might dispute the conclusions about American strategic incompetence reached by the Putin regime in Russia as well as its policies, the acuity of its analysis and its apprehensions for its own position as a result of what it believes to be the greatest threat Russia faces (i.e. Islamic terrorism in the guise of ISIS) continue to drive Russian policy on a daily basis throughout the greater Middle East.

Without a Strategy

U.S. strategists in the 1990s and 2000s argued that the victory in Desert Storm not only demonstrated the acknowledged technological and tactical proficiency and superiority of the U.S. Army, it also opened the way to a new period of war in which the U.S. would have total information superiority, clarity as to what was happening on the battlefield, and would reap the benefit of an unchal-lengeable technological superiority that enforced these conditions. This arrogant and unthinking mantra lay behind much of the thinking on Iraq and Afghanistan and now lies in the dust. As Colin Powell warned President Bush (43), breaking Iraq meant taking ownership of the problem and of its consequences that now include the increasingly visible destruction of both the Iraqi and Syrian states. But his warning was ignored.

The Obama Administration’s inability to formulate any kind of coherent strategy to deal either with the war in Afghanistan or Iraq and its complete mishandling of the Syrian crisis and failure to realize the need for a legitimate state after Qaddafi in the Middle East continues the tradition of misreading or disregarding the political essence involved in the successful waging of war. Not only do we now encounter a situation where states are falling apart before our eyes and producing the predictable Hobbesian results, we see such scourges as ISIS and chemical weapons on a daily basis. These phenomena confirm that where the state falls apart savagery becomes a norm if not the norm.

The Middle East as a Laboratory

Thus, the Middle East has been a laboratory for the idea that superior technology can bring about a strategic reordering of the region through the application of the tenets of the so-called revolution in military affairs (RMA). As that mantra failed, the U.S., confronted by classic guerilla warfare tactics, has struggled to find a label that encompasses the nature of the challenges that made its campaigns so difficult. Consequently, terms such as “asymmetric” or “hybrid war” emerged, or older terms such as “insurgency” and “counterinsurgency” were restored. One could fill libraries with the articles, papers, and books written on these topics. In that context, historians and commentators are still disputing whether the now famous “Surge” by U.S. forces in Iraq in 2007 generated anything more than a temporary and shallow stability in Iraq after that. But they cannot evade the fact that that the opportunities generated by the Surge have been squandered by both the Obama Administration and the Iraqi state, returning us to a situation in which one cannot honestly talk about victory in Iraq.

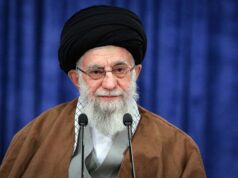

Yet regardless of the search for analytical labels, defeat and long-term anarchy throughout the region stare us in the face. Once again the laboratory experiment has failed, forcing us to go back to square one. And the results of a failed strategy, or the lack of one, have led the Administration to clutch at straws and launch what can only be described as a vast retreat of U.S. power. Whatever one’s position is on the recent agreement with Iran, it represents a retreat of U.S. policy and power and is acknowledged by all parties to entail those phenomena; hence the gloating Iranian statements that the Islamic Republic has prevailed. Moreover, the agreement appears to reflect a new idea: that over time it can be possible to bring about a modus vivendi with Iran that could lead to some sort of security cooperation (e.g. against ISIS) and resolving the Syrian nightmare. As far as the Middle East goes, this would amount to a contemporary reversal of alliances, and we can already see the fallout in the Israeli and Saudi reactions to U.S. policy.

Rapprochement with Iran

Arguably the rapprochement with Tehran, if one can call it that, represents another experiment undertaken with no sign of prior research or ideas as to what it will lead to—other than hoping or gambling that the Iranian political system will evolve in direction more acceptable to the U.S. As we should have learned, hope is not a strategy. So it is arguable too that the U.S. still has not grasped the critical need for strategy, or even what strategy is in the context of the issues of war and peace in the Middle East. Therefore until that situation changes, Washington will continue to be at the mercy of events and be obliged to improvise rather than to act with deliberation based on solid prior thought about the area.

This condition clearly reflects a bipartisan failure of both intelligence and policy. One of the original sins here is the never-ending conflation of policy and strategy with each other and with tactics. Space precludes an adequate definition of these terms but it should be clear to any reader that using these terms interchangeably or without reflection on their real meaning inevitably fosters confusion and bad political outcomes. While war remains, in Clausewitz’s terms, “actions taken by one party to force its will on a second party,” he also called it a “chameleon,” i.e. a shape-shifter. But there is an irreducible baseline that we cannot and must not shirk even when confronted by such a protean and dynamic phenomenon as Middle Eastern wars. A war in the Middle East, even if it is as necessary as was the war in Afghanistan, cannot be won and should not be launched without the most careful attention being paid to the development of the political instrument for which it is being fought.

The Results of War without Strategy

The utter blindness to what would be the future Iraqi state, and how it could be organized to foster peace and security, continues to haunt not just the United States but also the entire Middle East. It also led in many ways to the failure in Afghanistan, for resources vital to that effort were siphoned away before victory had been attained there. Indeed, we gave Bin Laden what he most wanted, namely a protracted war in the Middle East that has bled the U.S. of people and treasure while weakening it globally. Neither have we understood that no war in Afghanistan could be won without a viable indigenous governing mechanism, not one dependent on international relief agencies and Washington. Neither have we been able to come to grips with Pakistan’s nefarious role here. Indeed we are still trying to figure out what arms package we could devise to get Pakistan’s military—the real power in that country—to cooperate on our agenda even though they know better than we appear to realize that this agenda is inherently at odds with their perception of our vital interests.

Thus we are continuing to compound our errors even though our ability to obtain desired strategic results is eroding. In that situation other players—Iran, Russia, ISIS, and Turkey, to cite only some of them—are now endeavoring to carve out for themselves spheres of influence within which they feel they have to act in accordance with their vital interests. They will use whatever instrument of power comes to hand in order to impose some sort of order or regulate trends within those spheres. Unfortunately, those spheres overlap. Thus the withdrawal of the U.S. betokens more strife, not less. Thus the sunset of American power that has already begun is likely to give rise to a series of new experiments in regulating the Middle East that are as likely to fail as the previous ones. But it also has simultaneously become clear that theater conventional war is not dead as we see in Ukraine, that insurgency and counterinsurgency are not strategies but are elements of one. Neither are they the exclusive future of war. Nevertheless to wage either insurgency or counterinsurgency a real strategy is needed. That strategy may not and probably will not be foolproof, but without strategy we are flying blind.

To overcome the blindness that has afflicted U.S. policy during a generation of war, it is necessary to rejuvenate our capacity for developing strategists, teaching strategy—and not only to military officers—and clarifying our thinking. Good strategy may be an inherently difficult problem but it is not insuperable. But that is not the same thing as crafting sound policy, despite the close relation-ships between policy and strategy. They are not the same and if we are to succeed in the future we must recognize that fact The hubris of a technologically driven military perspective and the emphasis on a technique of fighting like counterinsurgency are predestined to fail. If we are going to be called upon, as well we might, in the future to fight in the Middle East, we must take to heart another one of Clausewitz’s maxims, namely that the first and most important task of the commander is to understand the nature of the war. Over the last generation we have signally and repeatedly failed to take this maxim to heart. Until we get it right we will continue to fail.

F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote that there are no “second acts” in American life. But in the Middle East, war is likely to be prevalent for years to come and likely to tempt if not drive America to participate. When and if that happens we had better get it right, for the consequences of another failure will be even worse than what we now see.

Stephen Blank, Ph.D., is Senior Fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council.