Unwelcome Back Carter

Jimmy Carter does not apologize for the historically inaccurate and inappropriate use of the word “apartheid” to describe the security wall that has effectively prevented Hamas suicide bombers from killing and maiming Israelis in restaurants and discotheques. He does not acknowledge that it has saved countless lives.

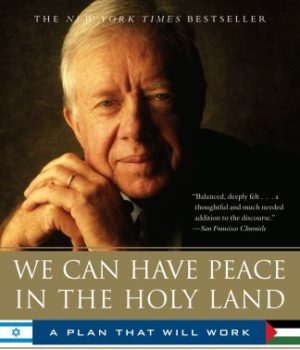

But this should come as no surprise. As with his last book, Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid, Carter doesn’t even feign a balanced approach to the Arab-Israeli conflict in We Can Have Peace in the Holy Land. He ignores the fact that a majority of Palestinians still refuse to accept the existence of the State of Israel, while insisting that peace would be achieved if Jerusalem would simply accede to the demands of the Palestinians. And because Israel refuses to unilaterally take those steps, We Can Have Peace in the Holy Land is a 180-page harangue of the Jewish state.

Part of the problem is that Carter is a man who once enjoyed prominence as a peacemaker – he presided over the 1978 Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt – but now lacks access to most of the power brokers in the Middle East. If one can somehow ignore the incessant snipes at Israel’s defense policies, the book reads like a tedious and depressing political diary of an elderly man who can’t quite remember where and when he misplaced his clout.

By Carter’s own admission, many high-level Israeli officials refused to meet with him during his “fact-finding” missions to the region. Similarly, officials from the George W. Bush administration kept their distance. The Palestinians, however, have Jimmy’s number. They continue to roll out the red carpet for him so he may regurgitate their narrative in provocative books in America.

By blindly embracing the Palestinian narrative, Carter does a grave injustice to the complex history and vexing dynamics of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. This short book may well have more errors and inaccuracies than pages.

Carter wrongly states, for example, that Hamas seeks to “remove Israel from the Holy Land using violence if necessary.” Actually, if Carter had bothered to read the Hamas charter, he would know that Hamas sees jihad as an imperative to destroy Israel and replace it with an Islamic Palestine. For Hamas there is no “if necessary.” War with Israel is its raison d’etre.

Carter also wrongly notes that the election of Binyamin Netanyahu as prime minister in 1996 “spelled the end of the peace process.” In fact, Netanyahu signed the Wye Plantation Memorandum of 1998, which perpetuated the Oslo peace process through the end of the decade.

He errs when he claims that Israel had an “iron grip on Gaza” in 2008, when in fact it unilaterally withdrew in 2005.

Carter erroneously writes that the Palestinians “returned peacefully to their homes with purchased goods” after breaching the wall separating Egypt from Gaza in 2008. In fact, the Palestinians brought huge quantities of long-range rockets, anti-tank missiles, anti-aircraft missiles and materiel for rocket production back into Gaza. Egyptian security forces also captured suicide bombing belts on Palestinians in the Sinai Peninsula, believed to be intended for Israeli or Western tourists at Egypt’s beach resorts.

Carter, who visited the Hamas terrorist organization against the expressed wishes of the State Department, also asserts that Hamas accepts Fatah faction leader Mahmoud Abbas as “spokesman for all Palestinians.” Carter somehow missed the civil war raging between Hamas and Fatah. Indeed, Hamas executed a brutally violent coup against Abbas’s faction in the Gaza Strip in 2007.

These sorts of errors, along with a plethora of other gross mischaracterizations and distortions, were exactly what prompted distinguished Emory University professor Kenneth Stein to resign from the Carter Center after years of dedicated service when Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid was released.

According to a rejoinder Stein published in Middle East Quarterly, “Carter allows ideology or opinion to get in the way of facts.” Stein then went about identifying “egregious errors of both commission and omission.”

In short, Carter has done it again.

Inexplicably, Carter also claims he is “no longer involved in partisan politics,” when in fact he is a superdelegate for the Democratic Party who actively endorsed the candidacy of Barack Obama and then vigorously opposed Obama’s consideration of Hillary Clinton as vice president. He is also the current and first-ever honorary chair of Democrats Abroad, an official organization of the Democratic Party that encourages expatriates to participate in the Democratic primaries and to vote for the Democratic candidate.

Once the reader wades through 173 pages of error-laden muck, Carter unveils his piece de resistance – the peace plan he proudly touts on the book’s cover. It is, in a word, vapid. It demonstrates no evidence of original thought. He merely apes what others have (unsuccessfully) proffered in the past, drawing heavily from parameters set forth in a Saudi proposal from 2002, a plan the Palestinians love because it requires few concessions on their part. Indeed, the Saudi plan calls for Israeli concessions and withdrawals in return for the possibility that the Arab states might accept Israel, but not necessarily as a Jewish state.

Carter’s latest will certainly not lead to “peace in the Holy Land.” Like his last book, it parrots the worst of the intransigent Palestinian positions, and offers nothing to forge common ground.

The writer, a former US Treasury intelligence analyst, is deputy executive director for the Jewish Policy Center and author of Hamas vs Fatah: The Struggle for Palestine.