Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad inaugurated a new policy yesterday encouraging population growth. Dismissing family planning as ungodly and a Western import, Ahmadinejad’s new initiative will pay families $950 for every newborn baby and deposit $95 into the child’s bank account every year until the age of 18. Family planning is “in the realm of the secular world,” Ahmadinejad said during the inauguration ceremony.

Iran’s first family planning policy, introduced in 1967 under Shah Reza Pahlavi, was aimed at accelerating economic growth and improving the status of women. The program was overturned after the 1979 Islamic Revolution by Ayatollah Khomeini, since family planning was then, like today, considered a Western influence. Iran’s population boomed, however, forcing Iran to revive its national family planning program by 1989.

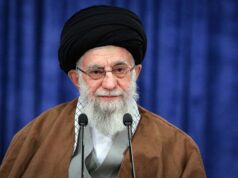

A veiled worker sorts condoms for packaging at the Takestan, Iran condom factory. |

|

Throughout the 1990s, Iran encouraged men and women to use free or inexpensive contraceptives. Such birth control methods are taught in a government class that is mandatory for couples to take before marriage. As a result, the government decreased the country’s population growth rate from its 1986 height of 3.9 percent to 1.6 percent in 2006.

What Ahmadinejad’s birth control reversal may illustrate, however, is that the president’s popularity is faltering, as his menacing attitude and actions towards the international community have brought sanctions onto the country. Indeed, this new birth program, which comes at a time when Iran is raising taxes, puts money in the pockets of the people and thus is seemingly geared toward the lower income segments of the population – the president’s backbone of support during the 2005 and 2009 elections.

Moreover, Ahmadinejad’s new program illustrates that since the 1979 revolution, the Iranian government has struggled to establish a national identity that combines Persian culture with Islamic revolutionary ideals. “From one president to another the whole orientation of the country changes,” said a prominent political scientist in Tehran, who asked to remain anonymous. “We do not have a consensus on who we are or where we are going. We can easily conclude that the ideological revolutionary order is an elite occupation, rather than a mass occupation,” he added.