Readers of Edwin Black’s chilling bestseller “IBM and the Holocaust” know that IBM was collecting data on Jews in Europe for Nazi Germany. Not just names, but whole families structures, addresses, business holdings, bank accounts, occupations, and language skills were tabulated on Hollerith machines. Beginning with census information in Weimar Germany, IBM, operating under the name Dahomag, branched out to the rest of Europe. With the Nazis rolling westward, Dahomag offices were well placed to provide everything required to round up the Jews (census tract information made it easier to figure out which streets to include in ghettos), send them efficiently to camps (Dahomag automated the train schedules), and confiscate their property. “We didn’t know how they knew,” was a common refrain from survivors.

IBM knew.

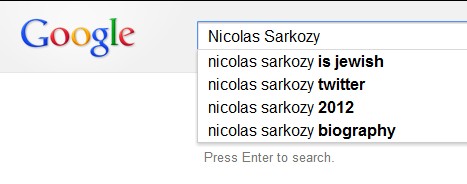

With that in mind, it doesn’t seem unreasonable to wonder about the “autocomplete” feature of Google that associates people with Jewishness. And in light of rising anti-Semitism in France and the monstrous murder of Jews, including children, outside a Jewish day school in Toulouse, it isn’t unreasonable to wonder who wants that information and for what purpose.

One French organization says Google is overseeing “the creation of what is probably the biggest Jewish file in history.” SOS Racisme is suing, saying Google users are “confronted daily with unsolicited and systematic associations between famous people and their Jewishness.” This, by itself, is hardly a crime. An interesting old list circulates on the internet providing the given name and the stage name of a variety of actors and actresses (mostly Jewish, some Italian), some of whom may have wanted to hide their origins and others who wanted to sound more “American.”

And Google, in its defense, says there are times when the autocomplete function for a word or topic will return no predicted searches. Google excludes what it calls “a narrow class of search queries related to pornography, violence, hate speech and copyright infringement.” It is hard to say that calling Jewish people “Jewish” is a hate crime, and even if Google’s algorithm makes a mistake, calling non-Jewish people “Jewish” is not hate speech either. So, says Google in essence, algorithms don’t target Jews; they’re just mathematical procedures.

Therein lies the moral dilemma: Only humans can take information and use it in the service of good or evil.

France, interestingly, was the solitary exception to IBM/Dahomag’s success in providing automated information to the Nazis. Rene Carmille, the then-comptroller general of the French Army, was a Dahomag man. In Lyon, he convinced the General Commission on the Jewish Question (GCJQ) that he could tabulate the information on French Jewry. Given 140,000 census cards at one point, he went to work, and work, and work, but no tabulated results emerged. Carmille, it turns out, was spending his time tabulating 800,000 former French soldiers on his Dahomag Hollerith machines – the backbone of the French Resistance. He also produced 20,000 fake identity cards for Jews and others seeking to escape persecution. He was discovered by the Nazis and died at Dachau in January 1945. Robert Carmille, who had worked on the project with his father, later said, “We never punched Column 11.” Column 11 was the column for religion.

In the ongoing tug of war between free speech and growing internet capabilities on the one hand, and personal privacy and possibly personal protection on the other, Google search has no Rene Carmille.