The Six Day War was the product of misconception, misunderstanding, mismanagement and mistakes by almost all the parties involved. The first major misstep was the Soviet warning to Egypt in early May 1967 that Israel had massed several brigades on its northern border and was prepared to attack Syria. The information was false, and the assumption of the Soviet leaders that they could win points with their Arab clients without unleashing the highly explosive emotions in the Middle East proved their total misunderstanding of the Arabs.

Following the Russian warning, Egypt’s president Gamal Abdel Nasser sent his armored divisions into the Sinai on May 15th. He repeated his actions of 1960 when, following an Israeli reprisal raid on Syria he had also dispatched his army into Sinai; he had then demanded that the United Nations remove their peacekeepers from their positions on the Egypt-Israel border and the Straits of Tiran on the Red Sea. But the secretary-general of the UN in 1960 had been Dag Hammarskjold, a smart diplomat who sent the peacekeepers to the UN camps in Gaza, where they played volleyball, basketball and got bored to death. Israel also reacted with restraint and only one armored brigade was dispatched to the southern border; while Prime Minister Ben-Gurion left for an extended trip abroad, stressing the fact that Israel was not taking the crisis seriously. A month later, the tension faded away, Nasser pulled back his army, and the peacekeepers resumed their positions and their duties.

But in 1967 the UN secretary-general was U Thant, a mediocre, dour, inflexible diplomat, totally misunderstanding the Middle East. It was his turn to make a major mistake. He told Nasser: either the peacekeepers stay where they are – or I shall remove all of them from Egypt. Nasser stuck to his position, and U Thant immediately ordered his peacekeepers out of the Sinai and Gaza.

Nasser’s mistake was next. Having acquired control of the Tiran Straits, he couldn’t help but close them to Israeli shipping. Israel had declared many times in the past that it regarded a closure of the Straits as casus belli, yet at that time Nasser still didn’t believe he was going to war.

Next in line – Israel. Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, a good man, a wise prime minister – but not a war leader – did not know what to do. He actually transferred all the defense and military decisions to Yitzhak Rabin, the IDF chief of staff, who could hardly cope with this burden, and collapsed for a short period. Eshkol also sent foreign minister Abba Eban to Paris, London, and Washington to ask for the help of the Western powers. That was a misconception at the cabinet level.

While the military assumed the Israeli army would be victorious in a war with Egypt, Israel’s civilian leaders desperately looked for help abroad. So Eban went on his tour. The British were sympathetic, but France’s president Charles de Gaulle openly moved to the side of the Arabs, decreeing a total embargo on weapons for Israel, whose military equipment was mainly French. De Gaulle also misread the situation; he told his aides that if a war erupted in the Middle East, Israel might be victorious in a first stage, but later the Arab armies would counter-attack, penetrate into Israel’s territory, America would have to intervene, and the world would have to face “a new Vietnam war.”

And in Washington, senior officials told Eban stories about “the Red Sea Regatta,” an international flotilla that would open the blockade on the Straits of Tiran.

These were stories and nothing else, and any astute observer should have understood from the first moment that America was going to do nothing. President Lyndon Johnson could make no move without the support of Congress, and it was clear that would not happen. Besides, very few nations liked the Regatta concept and were inclined to send their ships to the Straits.

And yet, President Johnson asked Israel to delay any action for another two or three weeks, while the United States tried to find a solution to the crisis. The Israeli cabinet met over and over again and agreed to wait. In the meantime Jordan, Syria and Iraq signed military agreements with Egypt, creating a united front against Israel. The writing was on the wall, and yet only two men in the Middle East apparently understood the situation.

One was Moshe Dayan, who told Rabin in a night meeting at his home that the only solution would be to go to war and destroy the Egyptian army.

The second man was an Egyptian: Mohammad Hassanein Heikal, the editor of the pro-government Al-Ahram newspaper and Nasser’s friend and confidante. Heikal’s analysis was clear and concise, and read like a mathematical formula. In an article headed: “Why war with Israel is inevitable,” he wrote:

Israel exists in the Middle East thanks to its power that deters the Arab states from attacking and destroying it. The massing of the Egyptian troops in the Sinai, the ouster of the UN peacekeepers, the closure of the Straits, the united front of Arab nations against Israel – all those have destroyed Israel’s deterrent force. If Israel wants to survive, she must restore her deterrent. To do so, she has to go to war. Therefore – war with Israel is inevitable.

The serial misconceptions did not spare the father of Israel, David Ben-Gurion. The “Old Man” believed that Israel shouldn’t go to war, and try to open the straits of Tiran, without obtaining the support of a Western power and making sure that the supply of weapons to Israel would continue. In a recorded interview with the author of this article, he spoke against any military action at the present time, assuming that the casualties of the Israeli army will be enormous – around 5,000 dead. He also bitterly criticized Rabin for mobilizing a small portion of army reservists. “You endangered the people of Israel!” he told Rabin, who held him in high esteem.

Yet, that was not the image Ben-Gurion projected. The people of Israel didn’t know that Ben-Gurion was against the war. In the eyes of many, he was still the tough, fearless leader who could stand up to the Arabs and lead Israel in the forthcoming war of survival. Editorials in major newspapers and citizens’ spontaneous petitions called for the replacement of the hesitant Eshkol with the resolute Ben-Gurion. Even Menachem Begin, the leader of the Likud and Ben-Gurion’s sworn political adversary, believed that the Old Man should return to the helm, and replace Eshkol as prime minister. In a dramatic move, he secretly came to Ben-Gurion’s house, willing to offer the Old Man the support of his party if he agreed to become prime minister again; but he was bitterly disappointed on hearing Ben-Gurion’s views. When the meeting was over, he told Shimon Peres, the secretary general of Ben-Gurion’s party, Rafi: “We remove our support from Ben-Gurion as prime minister, and transfer it to Moshe Dayan as minister of defense.”

In the meantime, winds of panic were blowing over Israel; journalists described future scenes of terrible destruction if the united Arab armies attacked, rabbis were consecrating city parks as emergency cemeteries, while high-school students were digging defensive trenches in the cities’ avenues. Newsreels and press photographs showed huge crowds dancing in the squares of the Arab capitals, waving flags and chanting slogans, hailing the imminent destruction of Israel by the victorious Arab armies. The people of Israel feared that the existence of their state, and their very survival, were in danger.

Eshkol slowly realized that war was inevitable. After a stormy meeting with the chiefs of staff, and an inconclusive vote in the cabinet, he sent the Mossad chief, Meir Amit, on a secret mission to Washington to probe the American views on a possible Israeli offensive. Amit met with several officials in the Pentagon, the CIA and the White House. He came back with the news that the “flotilla” project was stillborn; his talks in Washington, though, made him conclude that the United States would not object to an Israeli offensive.

The political pressure on Eshkol to appoint Dayan as defense minister kept mounting. Eshkol tried to resist, but under the pressure of his own party, he had to cede the defense portfolio to Dayan. And on June 5th, Israel attacked.

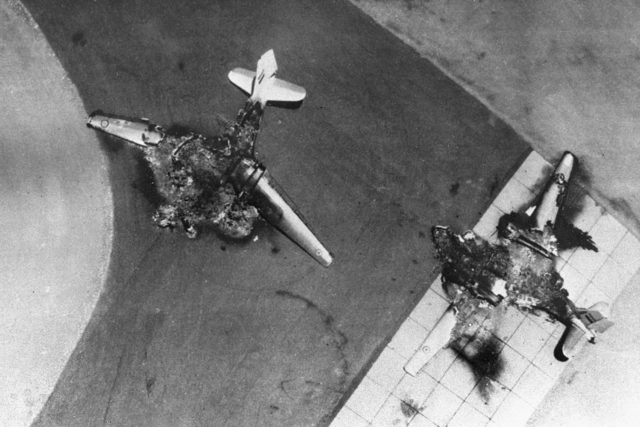

The war started with a stunning raid by practically the entire Israeli air force on Egypt’s air bases. That raid, meant to destroy the Egyptian air force on the ground, was the condition of a swift and total victory. The day before the raid, Rabin visited several air bases and told the young pilots: “Remember: your mission is one of life or death. If you succeed – we win the war; if you fail – God help us.”

The raid was utterly successful – in three hours the Egyptian air force had ceased to exist. A few hours later, both the Syrian and Jordanian air forces, that had tried to join in the battle, had been annihilated, as well as a part of the Iraqi air force.

Israel’s army, controlling the skies, made its way fighting through the Sinai and after a couple of days reached the Suez Canal. The “Shest,” the Soviet Sixth Fleet, suddenly appeared in the Mediterranean Sea, in dangerous proximity to the U.S. Sixth. The hotline between Washington and Moscow was activated several times, and some observers feared that World War Three might start at any moment; but as the top experts on Soviet policy predicted, the Russians refrained from taking military action, and limited their angry reactions to verbal attacks on Israel.

In the meantime, following Jordan’s attacks and bombardments, other Israeli units occupied the West Bank and took eastern Jerusalem. For the Israelis and Jews abroad, that was an impossible dream suddenly come true. In a last stage of the war, Israel conquered the Golan Heights.

On June 10th, the war was over, and Israel was stunned to discover it had an empire in its hands.

The postwar tragedy was that nobody in the Arab world was ready to negotiate for the return of the conquered lands. When the author of this article was appointed adviser to Moshe Dayan, the defense minister told him: “Michael, take your car and go see the West Bank before we return it.” (He was to become more hawkish later.)

Dayan also announced that he expected “a phone call from King Hussein.” But instead of calling Israel, the all-Arab conference in Khartoum, in August, decided there would be “no negotiations with Israel, no recognition of Israel, and no peace with Israel.”

An unexpected casualty of the war was David Ben-Gurion. When the war started, he wrote angry entries in his diary, harshly criticizing the leadership of the country, and predicting severe condemnations by the outside world. But as the fighting ended he realized that he had been mistaken, Israel had won, and there was a new team at the helm that had achieved a great victory. It seemed that history itself had confronted him and decreed: “Ben-Gurion, your time is over!” Six days earler he was still Israel’s greatest statesman, a candidate for the premiership of his nation. Now, he was a figure of the past, still admired and loved by many, but no more as an active leader. His contribution, though, was his lucid analysis of the new political situation. While most of Israel’s leaders were still drunk with victory and the return of Israel to its “biblical” borders, Ben-Gurion declared, over and over again, that in exchange for real peace Israel should relinquish all of the new territories, except for Jerusalem and the Golan Heights.

It would take 10 more years and another bloody war for Egypt to realize that it would have to pay the price of peace to get back its territories, and 27 more years for Jordan to make peace with the Jewish State. (Not before Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, in 1987, sabotaged a historic agreement between foreign minister Shimon Peres and King Hussein that could have brought peace to the Middle East).

And yet, the Arab Spring, the turmoil in Egypt and the civil war in Syria remind us how fragile and ephemeral peace in our neighborhood can be.

Michael Bar-Zohar, Ph.D., is an Israeli historian who served as a Member of the Knesset from 1981 to 1992.