At present, Venezuela is the only country in the world that is suffering from the ravages of hyperinflation. Alas, the word “hyperinflation” is thrown around carelessly and misused frequently in the financial press. Indeed, the debasement of language in the popular press has gone to such lengths that the word “hyperinflation” has almost lost its meaning.

So, just what is the definition of this oft-misused word? The convention adopted in the scientific literature is to classify an inflation as a hyperinflation if the monthly inflation rate exceeds 50 percent. This definition was adopted after Phillip Cagan published his seminal analysis of hyperinflation, which appeared in a book, edited by Milton Friedman, Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money (1956).

Since I use high-frequency (daily) data to measure inflation in countries where inflation is elevated, I have been able to refine Cagan’s 50 percent per month hyperinflation hurdle. With improved measurement techniques, I now define a hyperinflation as an inflation in which the inflation rate exceeds 50 percent per month for at least thirty consecutive days.

Calculating Inflation – PPP

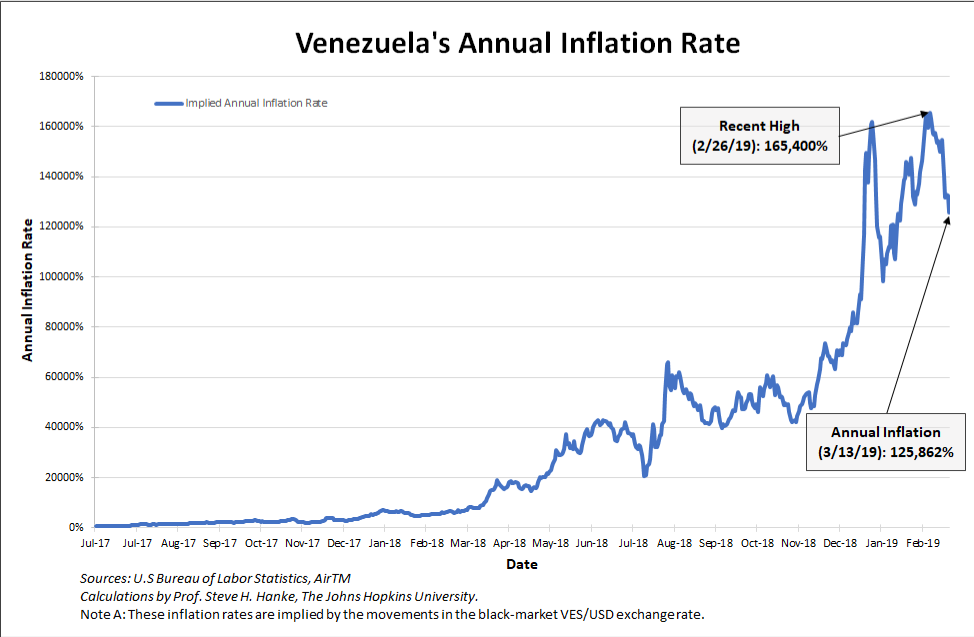

Just what is Venezuela’s inflation rate? Today, the annual inflation rate is 125,862 percent annually. How do I measure elevated inflation? The most important price in an economy is the exchange rate between the local currency – in this case, the bolivar – and the world’s reserve currency, the U.S. dollar. As long as there is an active black market (read: free market) for currency and the black market data are available, changes in the black market exchange rate can be reliably transformed into accurate measurements of countrywide inflation rates. The economic principle of purchasing power parity (PPP) allows for this transformation. The application of PPP to measure elevated inflation rates is both simple and very accurate.

Using evidence from Germany’s 1920-23 hyperinflation, my long-time friend, distinguished economist, and former Governor of the Bank of Israel Jacob Frenkel confirmed the accuracy of PPP during hyperinflations. In the July 1976 issue of the Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Frenkel plotted the Deutschmark/U.S. dollar exchange rate against both the German wholesale price index and the consumer price index. The correlations between Germany’s exchange rate and the two price indices were very close to unity throughout the episode of hyperinflation, indicating that changes in the inflation rate mirrored changes in the exchange rate.

Using evidence from Germany’s 1920-23 hyperinflation, my long-time friend, distinguished economist, and former Governor of the Bank of Israel Jacob Frenkel confirmed the accuracy of PPP during hyperinflations. In the July 1976 issue of the Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Frenkel plotted the Deutschmark/U.S. dollar exchange rate against both the German wholesale price index and the consumer price index. The correlations between Germany’s exchange rate and the two price indices were very close to unity throughout the episode of hyperinflation, indicating that changes in the inflation rate mirrored changes in the exchange rate.

Beyond the theory of PPP, the intuition of why PPP represents the ‘gold standard’ for measuring inflation during episodes of hyperinflation is clear. During those episodes, virtually all goods and services are either priced in a stable foreign currency (the U.S. dollar) or a local currency (the bolivar). In Venezuela, bolivar prices are determined by referring to the dollar prices of goods, and then converting them to local bolivar prices after observing the black market exchange rate. When the price level is increasing rapidly and erratically on a day-by-day, hour-by-hour, or even minute-by-minute basis, exchange rate quotations are the only source of information on how fast inflation is actually proceeding. That is why PPP holds and why I can use high-frequency data to calculate Venezuela’s inflation rate.

Duration Matters

Just how severe is Venezuela’s hyperinflation? Well, that depends on the metrics used to measure severity. If one looks at the rate of inflation itself, Venezuela’s hyperinflation is a bit above average. Of the world’s 58 episodes of hyperinflation that Nick Krus and I documented in the Routledge Handbook of Major Events in Economic History (2013), Venezuela ranks as the 23rd most severe hyperinflation.

But, if one measures severity by the duration of a hyperinflation, Venezuela’s episode, which started in November of 2016 and has yet to end, is rather severe. It has lasted for 29 months and counting.

So much for the definition and accurate measurement of Venezuela’s hyperinflation. What about forecasts for the course and duration of Venezuela’s episode? Well, even though you can measure a hyperinflation with great accuracy, you can’t reliably forecast what heights a hyperinflation will reach, or when those heights will be reached.

Surprisingly, that impossibility hasn’t stopped the International Monetary Fund (IMF) from throwing economic science to the winds. Yes, the IMF has regularly been reporting what are, in fact, absurd inflation forecasts for Venezuela.

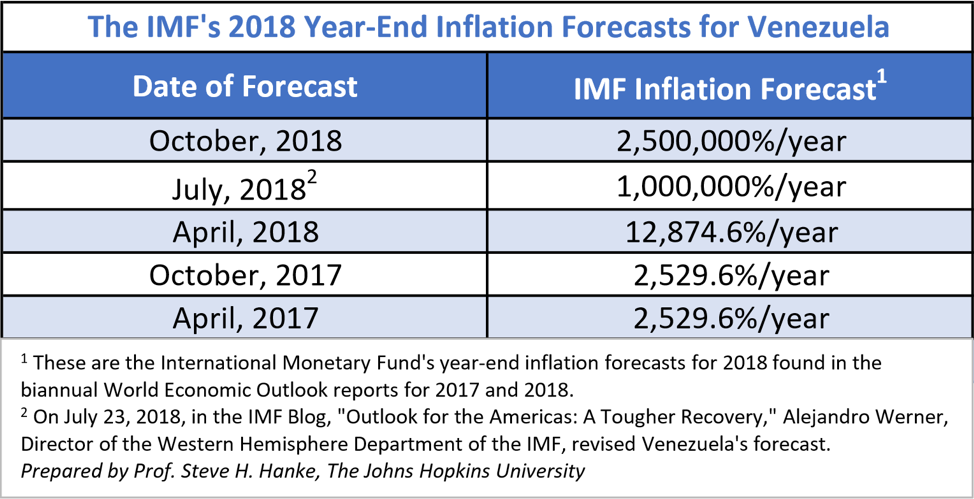

The table on page 19 contains five forecasts made by the IMF at different dates for Venezuela’s 2018 year-end inflation rate. The last IMF forecast was made in October, shortly before the end of the year.

Even a superficial examination of the table suggests that the IMF forecasts are problematic at best. Just look at the dramatic changes in the inflation forecasts—all made over a short period of time and for the same end date. The IMF’s absurdity comes into full view, however, when we compare the final year-end forecast value of 2,500,000 percent to the real measured year-end value of 80,000 percent annually. The IMF’s final forecast was not even in the same ball park as the measured value. Interestingly enough, the most inaccurate forecast made by the IMF was the one published in October 2018, just a few months before year’s end. As the IMF moved closer to the end date, the divergence between the forecast and the real measured rate widened.

As it turns out, one can accurately measure hyperinflations, but one can’t forecast their course or duration. The IMF has clearly failed to learn these lessons.

In any case, it’s clear that Venezuela’s big problem is hyperinflation. The first order of business for any new government in Venezuela will be to slay the hyperinflation dragon. This can be done within 24 hours with the introduction of a currency board.

A Currency Board

A currency board issues notes and coins convertible on demand into a foreign anchor currency at a fixed rate of exchange. As reserves, it holds low-risk, interest-bearing bonds denominated in the anchor currency. The reserve levels (both floors and ceilings) are set by law and are equal to 100 percent, or slightly more, of its monetary liabilities. So, the domestic currency issued via a currency board is nothing more than a clone of its anchor currency. A currency board generates profits (seigniorage) from the difference between the interest it earns on its reserve assets and the expense of maintaining its liabilities.

By design, a currency board, unlike a central bank, has no discretionary monetary powers and can’t engage in the fiduciary issue of money. It has an exchange rate policy (the exchange rate is fixed) but no monetary policy. A currency board’s operations are passive and automatic. The sole function of a currency board is to exchange the domestic currency it issues for an anchor currency at a fixed rate. Consequently, the quantity of domestic currency in circulation is determined solely by market forces, namely the demand for domestic currency.

A currency board can’t issue credit. Accordingly, a currency board imposes a hard budget constraint and discipline on the government. This is an underappreciated feature of currency boards. Unlike central banks, a currency board can’t be used as a means to finance government budgets.

Currency boards have existed in about 70 countries, and none have failed. The first one was installed in the British Indian Ocean colony of Mauritius in 1849. By the 1930s, currency boards were widespread among the British colonies in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Islands. They have also existed in a number of independent countries and city-states, such as Danzig and Singapore. One of the more interesting currency boards was installed in North Russia on November 11, 1918, during the civil war. Its architect was none other than John Maynard Keynes, who was a British Treasury official at the time.

Countries that have employed currency boards have delivered lower inflation rates, smaller fiscal deficits, lower debt levels relative to the gross domestic product, fewer banking crises, and higher real growth rates than comparable countries that have employed central banks.

To smash inflation and establish stability, a currency board for Venezuela would do the trick. Indeed, that’s why I proposed a currency board to Venezuela’s President Rafael Caldera when I was his adviser from 1995-96. The details of what I proposed then, and now, are contained in a book I co-authored with Kurt Schuler, Juntas Monetarias para países en desarrollo: Dinero, inflación y estabilidad económica, which was published in a second edition in 2015 by CEDICE in Caracas.

I know that currency boards work from, among other things, a great deal of personal experience in stopping hyperinflations—stopping them with the introduction of currency boards. One such case was in Bulgaria, when I served as President Petar Stoyanov’s adviser from 1997-2002.

Bulgaria

After Bulgaria took the exit from Communism in 1990, Bulgarians encountered some potholes. The economy plunged, there were debt defaults, and that Balkan paradise experienced an episode of hyperinflation. This episode peaked at an astounding 242 percent per month in February 1997. Yes, that’s per month.

With the expectation that a currency board would be the best system to crush Bulgaria’s hyperinflation, I wrote a book with Kurt Schuler that was translated into Bulgarian. In late 1996, it reached the top of the best-seller list in Sofia. In January 1997, I became President Stoyanov’s adviser. My primary tasks were to draft a currency board law for Bulgaria, and to explain to Bulgarian politicians and the public how such a system would halt the episode of hyperinflation.

Things moved rapidly. There’s nothing like a crisis to move the ball down the field. The currency board was installed on July 1, 1997, and inflation and interest rates plunged immediately. I can recall the genuine pleasure (perhaps relief, too) that President Stoyanov displayed when he congratulated me on the outstanding results produced during the first few weeks of the currency board. It was then that he confessed his hope that the currency board would kill inflation, but that he had reservations, and he was amazed when it worked even more rapidly than I had predicted. Much later, President Stoyanov confided that, without the stability created by the currency board system, Bulgaria would have had much more difficulty entering the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 2004 and the European Union in 2007.

Today, Venezuela should do exactly what Bulgaria did in 1997. A currency board would make the bolivar sound—a clone of the U.S. dollar, the world’s most important currency. With that, inflation would be smashed within 24 hours and stability would be established. And, while stability might not be everything, everything is nothing without stability.

The political forces behind the introduction of a currency board would be seen as credible in the eyes of Venezuelans. By amassing a huge stock of political capital for slaying the hyperinflation dragon, the politicians who introduce the currency board would be able to then begin to clean up Venezuela’s other messes. But, if the politicians fail to kill inflation first, there will be no successful reforms. That’s why a currency board is a vital first step for Venezuela.

Steve H. Hanke, Ph.D., is a Professor of Applied Economics at the Johns Hopkins University and is a Senior Fellow and Director of the Troubled Currencies Project at the Cato Institute.