Deeds Are Led by Words.

Sociopolitical developments of the past decades led to new arguments that have become part of hate discourse—namely, that European culture and traditions are being endangered by immigrants who will replace them. The argument expands the scope of existing hatred against African-Americans, Jews, and the LGBTQ community, and appeals to many. Participants in the new discourse enjoy a sense of belonging to a group of loyalists, sharing admiration of their heroes, and using jargon that has been newly developed, comprising catchy slogans, smartly coded acronyms, and visual symbols. Social media is being leveraged to quickly spread these messages to an eager audience of thousands. For example, a recent study shows that the number of tweets mentioning the “Great Replacement” conspiracy theory, which was introduced by Jean R.G. Camus in France in 2011, increased from 120,000 in 2014 to 330,000 in 2018 (mainly in Europe).

Thus, in recent years, prophets of this new white supremacist theory have been rather successful in disseminating their doctrine. They have convinced many that what they call “the White race” faces a concrete and immediate danger of losing its special status, or even the extinction of its identity and culture through “White genocide.” The declared enemies are not only these immigrants themselves but also those who enable immigration through their alleged global influence—that is, the Jews.

These apocalyptic depictions encourage urgent, concrete action, in order to overcome the danger. The arguments and symbolism developed by white supremacist groups have become effective in recruiting new supporters, instilling in their minds a sense of mission and urgency and driving some of them to action, namely carrying out terrorist acts against their perceived enemies. According to their statements, they hope to achieve the direct purpose of reducing the number of these enemies—including through the provocation of civil war in the United States—and the indirect aim of showing the way to others who would follow them. Following the 2019 El Paso Walmart shooting, a new level of alertness to the danger of white supremacist violence has been reached in the United States (e.g. “We Worked To Defeat The Islamic State; White Nationalist Terrorism Is An Equal Threat” in The Washington Post August 2019). There are indeed fundamental similarities between Muslim jihadi terrorists and white supremacist terrorists (noted for example in “Online Non-Jihadi Terrorism: Identifying Potential Threats,” by MEMRI May 2019). But regarding the vital struggle against their incitement in America there is an important difference: Unless they are jihadis, U.S. authorities will not act against domestic extremists spreading incitement. Thus, in his testimony in the Senate Judiciary Committee on July 23, 2019, FBI Director Christopher Wray stated clearly: “We, the FBI, don’t investigate ideology, no matter how repugnant. We investigate violence, and any extremist ideology, when it turns to violence, we are all over it.”

However, for its victims, when ideology turns to violence it is too late. In struggling against terrorism of both origins, one must first realize that deeds are led by words which, in turn, reflect ideology. This being the case, the struggle must start with fighting white supremacist incitement across social media. Thus, the authorities’ ability to do so effectively hinges on the criminalization of such incitement as it aids and abets terrorism. In the U.S. this is a formidable challenge, since freedom of speech is cherished by Americans across the political spectrum as an all-important pillar of American democracy.

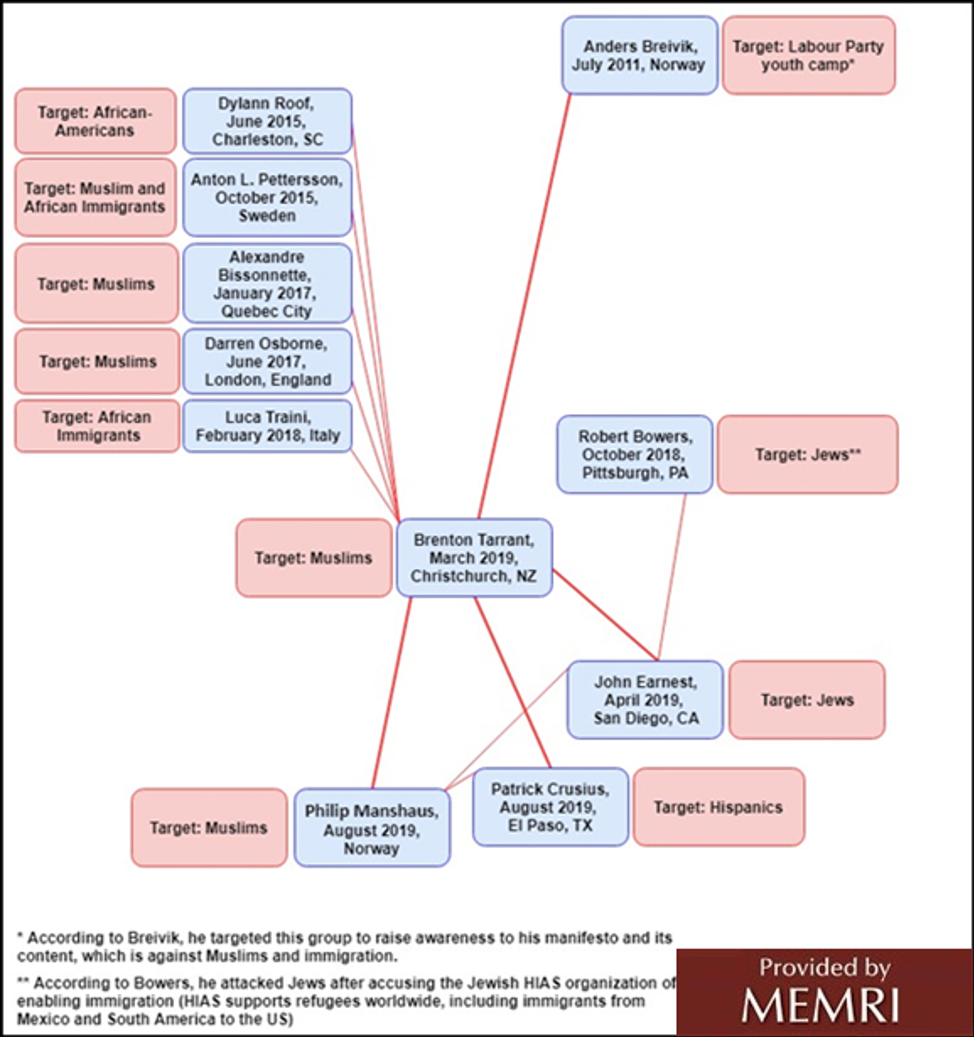

However, the 11 white supremacist terrorist attacks in this decade prove that circumstances have drastically changed. Some of these terrorists operated after careful selection of the locations and timing of their attacks: an African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) church, synagogues, and mosques—specifically during prayer times—or Latinos in a city known to host many of them. Hence, inciting against “the African-Americans,” “the Jews,” or “the Latino immigrants” can no longer be considered a general, vague threat. These terrorist attacks are directly influenced by white supremacist incitement and by previous attacks, even from overseas. The evolving reality calls for a fresh look into the legal tools needed to combat this danger.

White supremacist argumentation, jargon, and symbols are demonstrably both contagious and dangerous. Below is a brief look at main sources of inspiration for white supremacist terrorists who have acted since 2011:

Urgency

White supremacist propaganda creates the impression that the danger to what supremacists refer to as “the White race” is imminent, and that immediate action to reverse the process is needed. The indoctrination regarding the fate of the white majority in the United States includes: a countdown to the time when, according to statistical projections, the U.S. will no longer have a white majority, which is assumed will occur in 2045.

Inspiration Sources Cited by Perpetrators Themselves

The information that follows showcases the literature and terrorist attacks that have served as sources of inspiration for attacks that took place between 2011 and 2019. The information shows that in 11 attacks during in this time period, 184 people were killed and at least 387 others were wounded.

Publication of Mein Kampf, 1925

Adolf Hitler’s autobiographical manifesto, which outlines his political and ideological worldviews.

Publication of The Turner Diaries, 1978

The Turner Diaries, a novel by William Luther Pierce, outlines a civil war between the white supremacist “Organization” and the U.S. government (“The System”) which is controlled by Jews. In the book, The Day of the Rope, which takes place on August 1, is an event in which the white supremacists carry out brutal massacres, ethnically cleansing Los Angeles by killing its Jewish and black inhabitants, and publicly hanging people labeled “race traitors,” including federal officials and white women who have had relations with black men.

Pages of this book were found in the vehicle of Timothy McVeigh, who together with Terry Nichols bombed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995, killing 168 people and wounding approximately 700. David Copeland, a member of the neo-Nazi group National Socialist Movement, said he was inspired by the book to carry out the London nail bombings in April 1999, which resulted in the death of three people and wounded 140. This day was also mentioned by John Earnest, the Poway, California shooter in the manifesto attributed to him.

Publication of Siege, 1992

A collection of newsletters that James Mason wrote in the 1980s in collaboration with sect leader and mass murderer Charles Manson. With a focus on Holocaust denial and anti-Semitic and anti-gay themes, it calls for the establishment of a network of decentralized terror cells and for taking up arms against the “system.”

Publication of The Great Replacement, 2011

Camus’s book warns against the purported danger of the replacement of ethnic French people (i.e. Caucasian French) by immigrants from the Middle East and North Africa. According to his theory, these immigrants are purportedly aided by a trans-national group of globalist capitalist ruling elites called “Mondialists.”

Oslo, Norway attacks, 2011

Anders Behring Breivik carried out two sequential terrorist attacks. He first detonated a car bomb in Oslo, which killed eight people and wounded about 200. He then proceeded to the island of Utoya, the site of a summer camp run by the youth division of the ruling Norwegian Labor Party. He used semi-automatic weapons to fire on campers and staff, killing 69 and wounding 66. Breivik stated that he had chosen to target this group in order to raise awareness of his manifesto and his ideology, which is anti-Muslim and anti-immigration. He directly inspired Brenton Tarrant in New Zealand.

Overland Park Jewish Community Center shooting, 2014

Frazier Miller was a neo-Nazi who for many years preached hatred of Jews, and in 1987 wrote: “The Jews are our main and most formidable enemies.” In 2014, he shot dead three people close to the Overland Park Jewish Community Center, near Kansas City, Kansas They were later found to be Christians.

Charleston Church Shooting, 2015

Dylann Roof entered the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, shot dead nine people and wounded three during an evening Bible study. He claimed that his goal was to start a race war. His manifesto reflected many tenets of white supremacism, among them the belief that African Americans were raping white woman. He directly inspired Tarrant.

Quebec City mosque shooting, 2017

Alexandre Bissonnette entered the Islamic Cultural Centre of Quebec City, shot and killed nine and wounded 19 during an evening service. Bissonnette had been known to espouse far-right, white nationalist and anti-Muslim views, and had harassed Muslims on a Facebook page for refugees. He directly inspired Tarrant.

Stockholm truck attack, 2017

Rakhmat Akilov, a 39-year-old asylum seeker from Uzbekistan, hijacked a truck and deliberately drove into crowds along a central street, killing five people and wounding 14, including 11-year-old Ebba Akerlund. Tarrant wrote: “To take revenge for Ebba Akerlund.”

Finsbury Park attack, 2017

Darren Osborne drove into a crowd of Muslims leaving a mosque after prayers in Finsbury Park, London, killing one person and wounding nine others. He directly inspired Tarrant.

Macerata attack, 2018

Fascist activist Luca Traini shot and wounded six African immigrants in Macerata, Italy. He claimed to have done this to avenge the murder of 18-year-old Pamela Mastropietro, whom he believed had been murdered by an African immigrant. He directly inspired Tarrant.

Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, 2018

Robert Bowers entered the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, PA during morning services, allegedly shooting to death 11 people and wounding seven. He had been active on social media site Gab, posting anti-Semitic and white nationalist content. He directly inspired Earnest.

Christchurch mosque shooting, 2019

Brenton Tarrant entered the Al Noor Mosque and later the Linwood Islamic Centre during Friday services, where he shot dead a total of 51 people and wounded 49. In his manifesto, Tarrant expressed xenophobic and white supremacist sentiment calling for the removal of Muslims from European lands and including neo-Nazi symbols such as the Black Sun and the Cross of Odin. He directly inspired Earnest, Crusius and Philip Manshaus.

Poway, CA synagogue shooting, 2019

John Earnest shot and killed one person and wounded three others at Chabad of Poway synagogue in Poway, Cal., before his weapon jammed. He directly inspired Manshaus.

El Paso shooting, 2019

On August 3, 2019, Patrick Crusius entered a Walmart store in the Cielo Vista Mall in El Paso, Texas where he opened fire, killing 22 and wounding 24. A manifesto posted online just prior to the attack and generally attributed to him stated that the attack was inspired by Tarrant’s manifesto and was aimed against Latinos, calling them a threat to the future of white Americans. He directly inspired Manshaus.

Baerum Mosque shooting, 2019

Philip Manshaus entered the al-Noor Islamic Centre in Baerum, a town 13 miles outside Oslo, Norway, and opened fire. One person was wounded.

Idolization

A significant method of promoting and celebrating white supremacist ideology is by the attribution of sainthood to white supremacist terrorists. A meme posted online by Philip Manshaus before he carried out his Aug. 10, 2019 attack in Oslo showed Brenton Tarrant, the New Zealand mosque attacker, and his “disciples,” John Earnest, who murdered one person at the Chabad synagogue in Poway, Cal. and Patrick Crusius, who killed 22 at the El Paso, Texas Walmart. Tarrant is described as an “anointed Saint,” Earnest as the “first disciple of Saint Brenton” and Crusius as “directly inspired to fight back by Saint Tarrant.”

Conclusion

We opened by stating that deeds are led by words, but were careful not to claim that all inciting rhetoric leads directly to misdeeds. On the other hand, we demonstrated that those whose acts of murder were based on their ideological basis of “white supremacy” were indeed influenced by words to which they were exposed online.

It is difficult to estimate the number of those who consume venomous propaganda on a regular basis. For example, it can be assumed that millions of people are exposed to jihadist propaganda, but only very few are mobilized and perpetrate terrorist acts. However, such messages create a virulent atmosphere, which ultimately resonates with those few who resort to action. Replacing whole organizations and financing apparatuses, the Internet is now a most efficient multiplier of such propaganda; there would not have been a “world jihad” without this global loudspeaker.

Recall that not many acts of terror are needed in order to terrorize, destabilize and disrupt society. This is especially true when the perpetrators specifically target a certain defined group. Thus, the 2018 attack in the Pittsburg synagogue rippled across the Jewish community in the U.S. and the effect was exacerbated following the Poway synagogue attack only six months later. Combined with the increased level of online anti-Semitism, these two assaults led to a growing sense of emergency within the U.S. Jewish community and some steps were taken to protect it. Hence, it must be recognized that online incitement poses a real danger and should be treated accordingly.

Michael Davis heads the White Supremacist Online Incitement project for the Middle East Media Research Institute, Ze’ev B. Begin is a senior researcher for MEMRI and Yigal Carmon the president and founder.