Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this article appeared in the Transregional Threats Journal of the Center for a Secure Free Society (SFS); a national security think tank based in Washington, D.C.

On April 7, 2022, the United Nations General Assembly voted to suspend Russia from the Human Rights Council for its egregious human rights violations during the brutal invasion of Ukraine. Brazil, Cuba, El Salvador, Mexico, Nicaragua, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago, were not among the 93 countries that voted against Russia, highlighting Latin America as a problem for U.S. multilateral engagement.

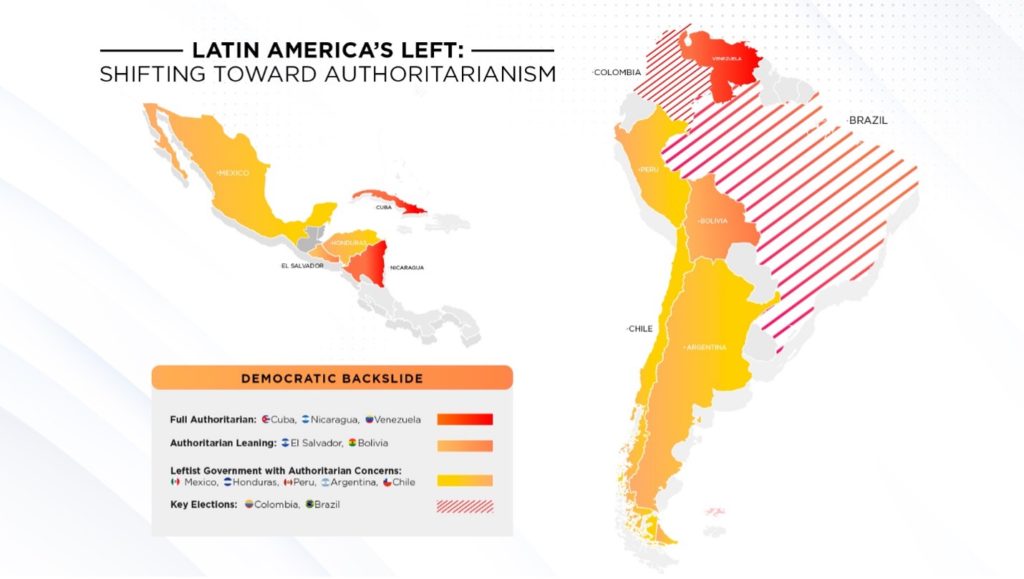

The vote also illustrated how the changing political composition of Latin America and the decline of democracy in the region impairs multilateral engagement that is critical to regional and global security.

It is largely a fait accompli that a majority of Latin America will be governed by leftist leaders, in what appears to be a shift away from the “conservative wave” that dominated the region in the second decade of the 21st century. Some, but not all these leftist governments have increasingly anti-democratic strains that have opened the door to global authoritarian actors, namely China, Russia, and Iran. The question, however, is whether the Latin American left will go in the direction of authoritarianism, much like Venezuela and Nicaragua, or seek to maintain the democratic institutions that afford the losing side the opportunity to regain political power?

The current state of affairs in Latin America offers both opportunities and risks for U.S. policymakers, as those committed to democracy on the Latin American left are in an internal struggle with the more authoritarian strains within its political current.

An Inflection Point

In the past five years, accelerated by the economic, fiscal, and sociopolitical stresses of the COVID-19 pandemic, leftist political parties have taken or regained power in a number of Latin American countries. These include Mexico, Honduras, Peru, Chile, Argentina, Bolivia, and Guyana. In others, such as Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua, they have consolidated autocratic control, often with ties to transnational organized crime.

In the former group, the orientation and composition of these leftist governments is mixed, or its recent arrival makes it too early to discern its final trajectory. In the latest cases of Honduras, Peru, and Chile, the United States is figuring out how to engage these new governments.

Inside the Washington Beltway, some U.S. policymakers and regional experts downplay concerns with Latin America’s left by emphasizing the democratic component of the new progressive governments in the region and the legitimate grievances that brought them to power. These experts often remind us about the American military interventions and other foreign policy blunders in Latin America in the past.

For the White House, the Biden administration arguably finds common cause with the region’s new leftist governments and its own economic and social policy agenda, hoping for opportunities to work with the new governments on issues like climate change, human rights, anti-corruption, and social justice.

Not all are so sanguine. Less optimistic policymakers and regional specialists, drawing insights from the recent record of leftist regimes in Latin America, see profound risks stemming from the potentially destructive policies of the new governments and their potential to generate crises that will pave the way for undesirable political change. This is compounded by a dangerous, anti-democratic minority within these new governments, inspired by Venezuela’s late authoritarian leader Hugo Chávez, and the intellectual and intelligence support of Cuba.

The concern is that this anti-democratic minority could hijack the new leftist governments in Latin America for their own political or criminal ends.

Both perspectives are partially correct. With a preponderance of Latin American countries currently controlled by the left, the dynamic between the more authoritarian-aligned actors and their potentially disastrous policies, and the more democratic counterparts in each country, will define the trajectory of the region for years to come. To understand these political changes and their implications for the United States, it’s useful to review recent actions by Latin America’s leftist governments. They present challenges and opportunities.

Latin America’s Left: A Survey

Latin America’s Left: A Survey

With the exception of the authoritarian regimes in Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua, the common element of left-oriented governments in Latin America, and those that may come to power in 2022, is the mixture within them of democratic actors versus autocrats whose policies would polarize society and radicalize its base.

This includes some with authoritarian tendencies who seek to deliberately hijack democratic institutions for malevolent ends. With this context, it is useful to survey the current political landscape of the Latin American left.

Mexico

In Mexico, political expression and competition by traditional parties such as the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party), PAN (National Action Party) and PRD (Party of the Democratic Revolution) continue to be viable. While President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) may be a popular president, he has sought to eliminate democratic obstacles to his policies.

In addition, AMLO has pursued economic policies that would marginalize Mexico’s deeply rooted private sector, including favoring statist approaches to the critical petroleum, electricity, and lithium sectors, among others, risking an economic crisis and increased polarization.

Honduras

The new government of President Xiomara Castro appears to be in an internal struggle between democratically oriented figures in her cabinet, such as Vice President Salvador Nasrallah, versus more radical actors, including her own husband and former President Manuel “Mel” Zelaya.

It’s worth remembering that Mel Zelaya was accused of receiving illicit funding from Hugo Chavez in Venezuela back in 2010. Similarly, it is believed that some of these radical elements within the new Castro government led the president to switch diplomatic recognition from the de jure interim government of Juan Guaido to the illegitimate regime of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela.

Peru

President Pedro Castillo, the politically inexperienced teacher from Cajamarca has arguably found himself in over his head with respect to the complex politics of Peru. To some degree, Castillo has tried to distance himself from Venezuela’s Chavista regime calling it “not the path to follow.” And he has tried to maintain his own voice against subversive influences within his political party, Peru Libre, such as Cuban-trained doctor Vladimir Ceron, pushing back against Ceron’s preferred cabinet picks.

The result has been political paralysis with a consistent stream of cabinet reshuffling, replacing a minister on average every nine days within his first nine months in office.

Argentina

President Alberto Fernandez initially presented himself to voters as a moderate within Peronism by contrast to his predecessor and now Vice President Christina Fernández de Kirchner, but after a couple years in power there are indications that the VP is increasingly calling the shots. Steadily increasing her influence within the government, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner allegedly pressured several changes to cabinet ministers in September 2021.

Alberto Fernandez’ controversial public overture to Russia’s Vladimir Putin during his state visit to Moscow and Beijing in February 2022 raised questions about the Argentine president’s judgement and moderation.

Chile

The most recent addition to Latin America’s left is the youthful Chilean President Gabriel Boric. The key partner within his Apruebo Dignidad coalition that helped achieve electoral success is the Chilean Communist Party and its influential leader Guillermo Tellier del Vale. Early in office, Boric had appointed far-left figures to key cabinet positions, although he has also reached out to moderates, and taken public positions against both Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine and anti-democratic regimes in Latin America.

While the Chilean Congress, currently dominated by the right and center-left, can challenge potential harmful policies of the new Boric government, this may tempt the millennial leader to leverage the ongoing process of changing the constitution to overcome that resistance.

The Constitutional Convention has already demonstrated a radical posture even beyond President Boric’s governing coalition, with policy proposals such as abolishing all existing Chilean government structures and replacing them with a “plurinational assembly.”

Two Key Elections

Last year’s presidential elections in Latin America saw a clean sweep by the region’s leftist political movements. The outcomes were also defined by an anti-incumbent vote that is a worldwide phenomenon prompted by the pandemic. This takes us to arguably the two most important elections in 2022, that of Colombia and Brazil, where the current right-leaning leaders run the risk of losing power to the Latin American left.

In Colombia, the ruling political party, Centro Democrático, lost a significant 21 seats in the March 2022 legislative elections. While in Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro trails in the polls behind the former leftist president Lula da Silva.

Colombia

Recent revelations that Russian criminal and intelligence operations in Colombia possibly contributed to last year’s violent street protests raises the stakes of this year’s presidential elections. The second round was set to take place on June 19 between Senator Gustavo Petro, a former M-19 guerilla leader, and businessman Rodolfo Hernandez. Petro has a sympathetic posture toward the dissidents of the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Columbia) and the ELN (National Liberation Army).

Senator Petro’s stated intention to end Colombia’s “carbon economy” including oil and coal, which account for a significant portion of the country’s exports, would likely exacerbate an already grave economic and fiscal situation and provide fodder for more social unrest throughout the country.

While some polls initially put Hernandez ahead for Round 2, Petro received more than 50 percent of the vote, beating Hernandez by 3 percentage points, and leading Hernandez to publicly accept the results, reducing the prospects for significant election-related violence. While Petro will almost certainly bring significant change in Colombia’s internal policies and external engagement, the President-elect was initially conciliatory, saying that “Peace means a Colombian society with opportunities. Peace means that someone like me can become president or someone like Francia can be vice president. Peace means that we must stop killing one another.”

Brazil

The time that former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva spent in prison due to his (subsequently suspended) corruption conviction means that his possible victory in Brazil’s October 2022 presidential election could make him far more disposed to adopt a radical left posture than during his 2003-2010 prior period in office, although his victory is not guaranteed.

Some believe he would pursue a moderate course similar to that of his previous term . On the other hand, like Michelle Bachelet in Chile during her second period in office, Lula’s age (currently 76) means that this would likely be his last tenure as president, tempting him to pursue an agenda more consistent with his posture in the 1980s and 1990s when he was a proud socialist calling on Brazil to default on its foreign debt.

Indeed, Lula’s public statements about prioritizing the need to reduce poverty over fiscal responsibility already suggest Lula’s public intention to depart from his prior pragmatism.

Implications for the United States

The political panorama in Latin America is all the more important when considering the geopolitical scenario and current global events, none more pressing than the war between Russia and Ukraine. Russia has been encroaching on Latin America for several decades, shoring up allies throughout the region. It has turned to these allies as the conflict intensified in Ukraine.

On February 25, the Organization of American States (OAS) issued a declaration condemning the Russian attack on Ukraine and calling on Russia to cease its hostilities. Notably missing from support of the OAS resolution were Bolivia, Brazil, El Salvador, Honduras, St. Vincent and Grenadines, and Nicaragua, highlighting how the changing political composition of Latin America and the decline of democratic governments has impaired multilateral and multidimensional security.

Less than a week later, some of these same countries abstained from an important vote in the United Nations to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The Biden administration’s focus with Latin America on the issues of human rights, anti-corruption, climate change, sustainable development, and social justice is not inherently wrong. Yet, it’s important for the administration to develop a regional strategy based on balance while carefully thinking through U.S. strategic interests in Latin America vis-à-vis our near-peer adversaries, Russia, and China.

Two key considerations should shape those tradeoffs: First, The Biden administration must not confuse respect for the sovereignty of its partners in Latin America, or its sympathy with their political agenda, with turning a blind eye to the dangerous autocratic minority within each leftist Latin American government that would polarize, paralyze, or hijack the region’s democratic institutions for their own often malevolent ends.

And the Biden administration must think strategically with respect to how it pressures its partners, particularly when such interference politically undercuts friends of the United States, who, however imperfect, are critical to regional peace and stability. The risks of bringing to power those in the region more disposed to pursue policies that move away from democracy and cooperation with the United States and open the door to malign types of cooperation with extra-hemispheric American rivals, is greater than specific differences with any particular government in Latin America.

R. Evan Ellis, Ph.D., is a research professor of Latin American Studies at the U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute. He previously served on the Secretary of State’s policy planning staff with responsibility for Latin America and the Caribbean.