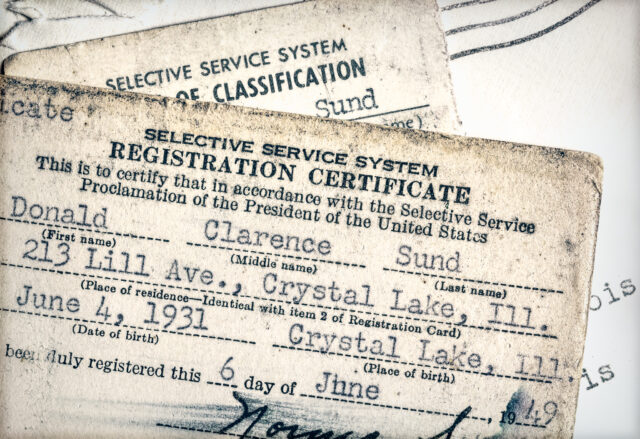

Most Americans are not aware that all men ages 18 to 25 have a legal obligation to register in case of a draft. Although the draft was abolished in 1973, selective service was resumed in 1980, when after the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan a capability to conscript was again deemed critical to the national defense. The system for registering for selective service is passive, it occurs when you apply for your driver’s license or federal student aid. Most American males aren’t even aware that they’re registered for the draft.

Under the military’s current standards, 71 percent of Americans ages 17 to 24 do not meet the physical or mental qualifications for military service. People often assume the draft was compulsory for an entire generation, but this was never the case. Of those killed in Vietnam, the war most inextricably linked to the draft, 69.6 percent were volunteers.

To wage war America has always had to create a social construct to sustain it, from the colonial militias and French aid in the Revolution, to the introduction of the draft and the first-ever income tax to fund the Civil War, to the war bonds and industrial mobilization of the Second World War. In the past, a blend of taxation and conscription meant it was difficult for us to sustain a war beyond several years. Neither citizens nor citizen-soldiers had much patience for commanders, nor commanders-in-chief, who muddled along.

Take, for example, Washington before he famously crossed the Delaware, reading Thomas Paine’s The American Crisis as a plea to his disbanding army (“These are the times that try men’s souls…”). Or Lincoln, whose perceived mismanagement of the Civil War made his defeat in the 1864 presidential election a foregone conclusion (until Atlanta fell to the Union a few weeks before the vote). The history of American warfare—even the “good” wars—is a history of our leaders desperately trying to preserve the requisite national-will because Americans would not abide a costly, protracted war. This is no longer true.

Today, the way we wage war is ahistorical—and seemingly without end. Never before has America engaged in a protracted conflict with an all-volunteer military that was funded primarily through deficit spending. Of our $33 trillion national debt, approximately $6 trillion is a bill for the post-9/11 wars. These became America’s longest, with Afghanistan surpassing Vietnam by thirteen years. And it’s been by design. In the aftermath of 9/11 there was virtually no public debate about a war tax or a draft. Our leaders responded to those attacks by mobilizing our government and military but when it came to citizens, President George W. Bush said, “I have urged our fellow Americans to go about their lives.” And so, the war effort famously moved to the shopping mall.

In fairness to Bush, when read as a response to a terrorist attack designed to disrupt American life, his remarks are understandable. However, when read in the context of what would become a two-decades long military adventure, those same remarks seem negligent, even calculated. This is particularly true for a generation of leaders (both Republican and Democrat) who came of age during Vietnam, when the draft itself and the indignation it caused mobilized the Boomer generation to end the war, one that otherwise might have festered on.

If after 9/11 we had implemented a draft and a war tax, it seems doubtful that the Millennial generation would’ve abided two decades of their draft numbers being called, or that their Boomer parents would’ve abided a higher tax rate to, say, ensure that the Afghan National Army could rely on US troops for a fifth, tenth, or fifteenth fighting season in the Hindu Kush. But deficit spending along with an all-volunteer military granted successive administrations a blank check with which to wage war.

Militarized ‘Peace’

And wage war they have. Without congressional approval. Without updating the current Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) which was passed by Congress days after 9/11. Currently, we live in a highly militarized society but one which most of us largely perceive to be “at peace.” This is one of the great counter-intuitive realities of the draft. A draft doesn’t increase our militarization. It decreases it. A draft places militarism on a leash.

In the run-up to the 2018 midterm elections, 42 percent of Americans didn’t know whether or not we were still at war in Afghanistan. There are few debates in public life that should merit greater attention from its citizens than whether or not to commit its sons and daughters to fight and possibly to die. Imagine the debate surrounding troop levels in Iraq, or Syria, or the Horn of Africa if some of those troops were draftees, or if your own child were eligible for the draft. Imagine if we lived in a society where the commitment of eighteen and nineteen-year-olds to a combat zone generated the same breathless attention as college admissions. Imagine Twitter with a draft going on; who knows—“helicopter parents” combined with Millennial and Gen Z cancel-culture could save us by canceling the next unnecessary war.

After Vietnam, when President Nixon eliminated the draft, the US military was in shambles. It had morale problems. Drug problems. Racial problems. It had lost America’s first war and with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and our failed bid to rescue our hostages from Tehran on the horizon, it seemed poised to lose the next one. From the detritus of the post-Vietnam military, a generation of officers—Colin Powell, Norman Schwarzkopf, Anthony Zinni, to name a few—began the decades long work of thoroughly rebuilding and professionalizing its ranks. The most visible result of their toil played out in 1991, with scenes of ultra-sleek US battle tanks equipped with hydraulically stabilized cannons zipping across the Kuwaiti desert at 50 miles-per-hour, trouncing the Iraqi military (the world’s fifth largest at the time) in a whopping 100-hour-long ground war. More recently, we saw the high-tech efficiency and lethality of our military in its rapid ouster of the Taliban from Afghanistan in 2001 and its rush to Baghdad in 2003.

Today, among many officers, particularly those senior officers who shepherded in that change, the idea of returning draftees to the military seems entirely regressive. Why would you degrade the finest fighting machine the world has ever known? It’s not a logic without merit, but professionalization has had its own drawbacks, ones that are perhaps more insidious to the fabric of a democracy than a draft.

Not long ago, I was speaking on a panel about the integration of women into frontline combat units. The Department of Defense had recently approved its new policy, and I argued that it was the military’s job—particularly that of my own service branch, the Marine Corps, which began implementation at a stubborn pace—to execute and support that policy, regardless of their reservations. A retired Marine colonel in the audience became incensed. He stood, prodding: On average women weren’t as strong as men. Could I deny this? Of course, no. Men and women were often sexually attracted to one another. Could I deny this? Also, no. Then how could I argue for integration when it would so clearly degrade our ability to fight and win wars?

I replied that our military didn’t exist solely to fight and win our wars. Our military was also a representation of us, which counted for quite a lot.

The colonel then turned to the crowd and, as if to prove his point, announced that if we took all the women in the room and pitted them against all the men in a “fight to the death”—right then and there—that everyone knew who would win.

More than One Mission

The idea that the military exists solely to fight and win our nation’s wars is as juvenile as the colonel challenging the audience to throw down for a battle of the sexes deathmatch. Might makes right is not the policy of the US government, or at least shouldn’t be. If our military doesn’t represent our values, it can threaten to undermine them. The founding fathers understood this. They were suspicious of standing armies. It’s a suspicion we’ve since shrugged off, one only need visit a major sporting event to witness the fetishization of our military.

The concern about degrading our military’s capabilities through a draft is legitimate. However, conscription has only ever been used in this country to augment a core force of volunteers, and often to great effect. Our military, which in World War II fought twin theater wars in the Pacific and Atlantic, was 61.2 percent conscripted. That percentage was 23.9 percent in Vietnam. The question then becomes: could you introduce a certain number of conscripts into the all-volunteer military at a lower rate without a meaningful degradation in its capability? And what would that rate be? Ten percent (130,000 people), five percent, (65,000 people), one percent (13,000 people), and would those numbers be meaningful?

What would be most meaningful might not actually be the number of individuals drafted, but the specter of the draft itself. The idea that citizenship has a cost, that you owe something to society, leads to the question of who owes what?

One of the central criticisms of the Vietnam-era draft was that it drew disproportionately from those of low socio-economic backgrounds, while the children of the wealthy and influential were able to finagle exceptions. Under rules promoted by then-Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, draft boards across the country were required to call up men with IQ scores below the minimum standards to offset the student deferments that were offered to those with higher IQs who met standards but had the benefit of being able to afford college. Take for instance Harvard University, from which 19 alumni were killed in Vietnam, compared to Thomas Alva Edison High School in Philadelphia, which was predominately African-American and had the highest death-rate of any high school in the nation, with 64 killed, despite its smaller relative size.

Who gets drafted has always been just as important as whether or not there is a draft. In conflicts like Vietnam and the Civil War, the draft exacerbated social inequalities by providing exemptions for the wealthy and influential. A certain type of draft could, however, become a tool to promote greater equality. It could create greater social cohesion. And, lastly, it could create greater accountability between our policies and our population. In the era of the one-percent, of hyper-partisanship, of identity politics and divisiveness, a reverse-engineered draft could prove a powerful tool to counteract these corrosive forces.

Reverse-Engineered Draft

Here’s what a reverse-engineered draft could look like:

The Department of Defense would annually set a certain number of draftees for induction into the Armed Forces for two-year enlistments, which is half the typical enlistment of a volunteer. This number would be kept small as a percentage of the overall active duty force, let’s say five percent, or 65,000 people, which is about the size of the Coast Guard. By keeping the number small we would retain the culture of professionalism born after the troubles of the post-Vietnam military. Upon induction, new servicemembers are then, typically, assigned military occupational specialties, like medic, or truck driver, or radio operator. However, in the past, another way people gamed the draft was to gain cushy assignments through influence within the military. In a reverse-engineered draft, inductees would only be eligible for military occupational specialties within the combat arms—infantry, tanks, artillery, and the like. And with the recent integration of women, the gender-divide would no longer be an issue as women would also be eligible not only for the draft but also for frontline service.

And no one could skip this draft unlike previous drafts where through the practice of hiring substitutes during the Civil War, or college deferments during the Vietnam War, the well-heeled adeptly avoided conscription. This placed the burden of national defense on those with the least resources. And when those wars turned to quagmires, elites in this country—whose children did not often fill the ranks—were less invested in the outcome.

Which comes to a final, essential aspect of the reverse-engineered draft: those whose families fall into the top income-tax bracket would be the only ones eligible. These are the children of the most influential in our country, those whose financial success in business, or tech, or entertainment, have placed them in a position to bundle political contributions among their friends, or have a call returned by a senator or member of the House. These are the helicopter parents, a demographic that does not sit idly by with regards to their children’s well-being.

The military does—as the agitated colonel pointed out—exist to fight and win our nation’s wars. But it is also one of our great engines of societal mobility. Those who enlist are taught a trade and if they earn an honorable discharge they’re granted tuition for college under the G.I. Bill. From the greatest generation to my own millennial generation, the social result has been transformative. And the military will continue to attract the professionals who wish to serve out a 40-year career, as well as the ambitious citizens who wish to pull themselves up by their bootstraps with a four-year enlistment and G.I. Bill. Our military continues to be an engine of societal mobility, but it also needs to return to being what it once was, a societal leveler, in which men and women of diverse backgrounds, at an impressionable age, were forced together in the pursuit of a mission larger than themselves.

Why send our sons and daughter to fight and die in the name of unity? Couldn’t they sign up for Habitat for Humanity? Yes, they could, and opportunities to serve outside the military will still be important. However, an argument for mandatory national public service that excludes military service forgets perhaps the most important consequence of a draft, which is that with a draft the barrier to entering new wars would be significantly higher.

Elliot Ackerman is a former Marine Corps special operations team leader and is a best-selling author.