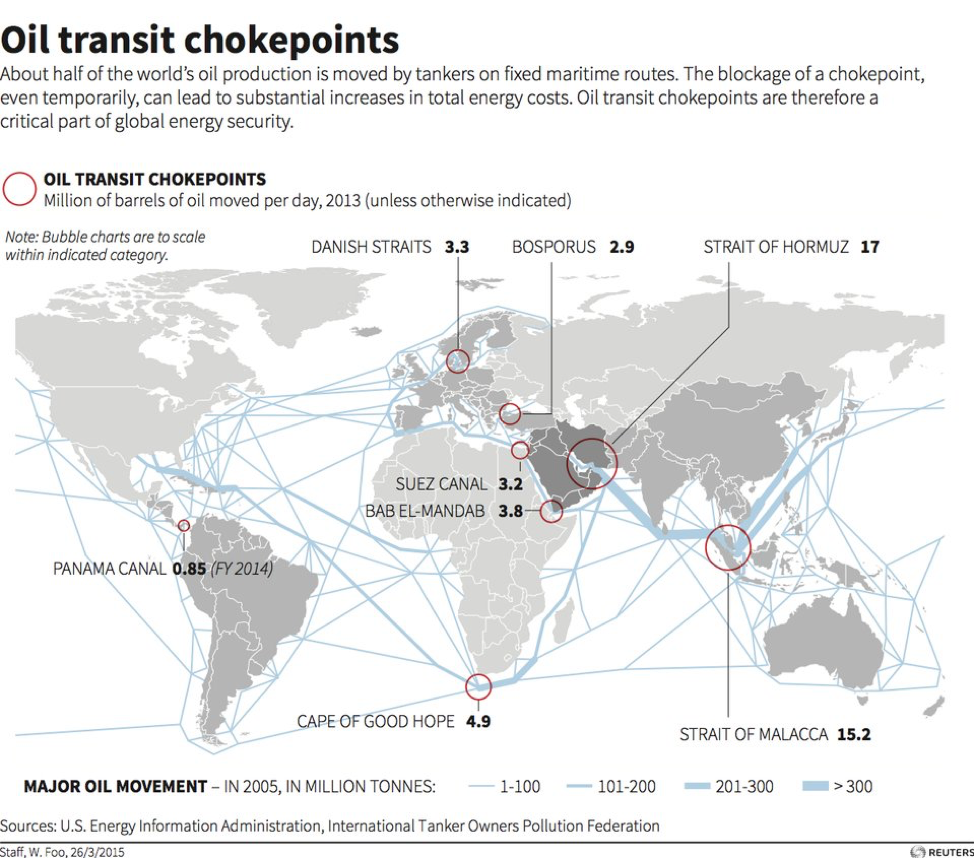

Since 1974, interference in maritime oil transportation has been a factor in U.S. economic recessions. This interference has often been closely connected to the narrow straits or choke points through which more than half of the world’s daily oil production passes by commercial tanker.

Despite great progress in expanding U.S. domestic oil production, we cannot escape the effects of such possible future interference. That’s because we are still a net importer of crude oil, upwards of 10 million barrels a day – although over the past few years we have become far less dependent on foreign sources.

The Straits of Hormuz and Bab el-Mandab are key maritime chokepoints where Russia and Iran have a history of interference with oil transportation. Iran has most recently been copying such activity as well in the Straits of Gibraltar. A take-over of Morocco by the rebel Polisario Front would put another rogue state astride a key oil route and add another vital “strait” increasingly vulnerable to hostile interdiction.

The Straits of Denmark, around the Cape of Good Hope along-side South Africa, and the Panama Canal are other straits through which large quantities of oil move daily, but remain historically relatively free of interference.

However, one worrisome and emerging factor is China’s militarization of its illegal and artificial South China Sea islands, along with new Chinese military bases in East Africa, both of which give Beijing leverage over the maritime oil traffic moving through the Bab el-Mandab (Red Sea) and the Straits of Malacca, two critical global chokepoints.

The United States and its allies thus need to carefully watch the world’s key maritime chokepoints as interference with oil tanker traffic can buffet the world’s top industrial economies and trigger crippling economic recessions. And as we have seen just recently, Iran has shown itself ready to partially cripple oil production (a cut of 5 million barrels) and transportation, attacking tankers and now apparently launching missile and drone attacks against two key Saudi oil facilities—the Khourais oilfield and Abqaiq processing center. Closing the Straits of Hormuz, by comparison, would be the equivalent not of taking 5 million barrels of oil off the market each day but between 17-20 million barrels, fully 20 percent of daily world production.

Vulnerability of Maritime Commerce

In 1961, all U.S. imports and exports totaled $50 billion annually. U.S. trade now exceeds $5.6 trillion, a 1,100 percent increase. Particularly noteworthy over this time has been the growth in the U.S. import and export of oil and petroleum products, in 1961 under $10 billion and now at $368 billion. All this oil now moves through eight key maritime choke points, which if blocked can skyrocket oil prices. [Editor’s Note: Numbers are unadjusted for inflation.]

For the United States this had become a growing strategic consideration. From 1961 until recently, U.S. exports of petroleum products diminished markedly while imports soared, growing from 365 million barrels in 1961 to 3 billion barrels in the past decade. As Robert Zubrin noted in a Jan. 16, 2012 National Review essay, U.S. economic recessions in 1974, 1980-81, 1990-91, 2000-01, and 2008-09, all were preceded by a dramatic increase in oil prices, and most of those spikes occurred because oil maritime transportation through these straits was either shut down or curtailed.

By mid-2008, for example, oil prices had run up to $147 barrel by July 4, followed by major Saudi production increases that dropped oil prices to $32 but not quickly enough to avoid a major recession.

The lowered price of oil did not sit well with the Russians, as oil at $50 barrel barely allowed Moscow to pay its most pressing bills, given that half of the country’s government income depended upon oil and gas sales. As a result, Russian assisted Somali “pirates” started seizing oil tankers traveling through the Straits of Hormuz and into the Arabian and Red Sea area, respectively to artificially elevate the price of oil. Seizing tanker traffic in narrow straits areas is much easier than doing so on the high seas.

Now, with the Somali pirates less a factor, the assumption remains in much of the academic, intelligence community, public policy groups, Congress, the entertainment industry, and the news media that interruptions of commercial and cargo sea traffic including oil, are a thing of the past. It is assumed that even rogue or adversary nations (Iran for example) do not want oil resources or trade interrupted because the resulting oil price spikes or interruption of commercial ocean-going trade just causes too much economic dislocation.

Is this true?

When the Somali pirates starting grabbing oil tankers in the Hormuz Straits and Persian Gulf area, global oil prices remained stuck at over $100 barrel, a not-so-inconsiderate factor in the record slow growth and recovery of the 2009-16 period, an economic performance that had lower economic growth compared to any other economic recovery since World War II. And now, multiple Iranian attacks on maritime oil traffic and oil production illustrate Iran has joined the disruption team as well.

Is America Still Vulnerable?

However, with the widespread development of fracking (hydraulic fracturing) in the United States, and with American natural gas and oil production dramatically increasing, concerns over oil availability and price have largely dropped off the radar screen. U.S. oil and gas production have reached a record high in excess of 12-17 million barrels per day, the highest in the world. Many analysts now believe America is immune to oil price disruptions whether as a result of war, terrorist attacks, or deliberate cuts in production.

But as Anthony Cordesman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies explains, the United States is not immune to the world market price for oil. One cannot have a U.S. domestic market in one price (because we export and import very large amounts of oil) while the rest of the world has another price. That is why the Iranian attack in September spiked oil prices everywhere, including in the United States, but given this country’s huge growth in oil production and emergency supply from the strategic petroleum reserve, the reduction in Saudi production did not panic world markets nor cause immediate shortages in the United States.

Therefore, despite the great news that America leads the world in petroleum and natural gas production, the U.S. economy is not necessarily immune to the machinations of the oil markets in which adversaries such as Russia, China and Iran play a prominent role. Especially if the flow of oil is stopped through key straits by military action that does in fact panic world markets.

As previously noted, Russian naval Spetsnaz graduates were assisting “Somali” pirates seizing large crude oil carriers. This helped drive oil prices to $148 barrel on July 4, 2008. Despite the Saudi government pushing up production dramatically to stave off a serious recession, the help was too late. Even oil at $32 barrel could not eliminate the sharp recessionary economic factors that caused one of the most serious economic downturns in the post-World War period.

Emerging Iranian Maritime Strategy

The Iranians have not only seized oil tankers, but they have also begun to talk about being a toll collector for commercial sea-going traffic through the Straits of Hormuz, as well as granting preferential access to the area. This threat was considered far beyond Iran’s military capability until they “invited” the Russians to locate military forces on two Iranian bases on the shores of the Persian Gulf.

Collecting tolls in the broad expanse of the oceans makes no sense. But to do so in the area of key narrow straits or chokepoints around the globe, that is a serious threat. Iran has added an additional factor of going after adjacent land production facilities, raising even further the specter of what I term economic IEDs (improvised explosive devices) as a means of Iran using oil blackmail to get its enemies to do its bidding.

Moving to the other side of the Indian Ocean, says China expert Rick Fisher, Chinese ballistic missiles threaten the entire Malaccan Straits. This would be especially so if deployed on the artificial islands built by China in the South China Sea.

Other Rogue State Imitators

What is interesting is how quickly oil prices can rise once interference with maritime tanker shipping occurs. As I wrote in 2010 for the Gatestone Institute:

In late August and early September 2008, the Saudi government pledged to the Bush administration that oil production in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia would be pushed upwards of 2 million barrels a day greater than the allowable OPEC targets.

When, on October 21, 2008, the Director-General of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, Abdalla Salem el-Badri, went to Moscow, OPEC wanted Russia to cut production. Russia said no. Moscow then accused the Saudi government and OPEC of vastly exceeding their quotas for oil production, thus pushing down the price of oil.

Although true, the head of OPEC countered by noting how ironic that Russia—although not a formal member of OPEC—was also pumping oil as fast as it could. The Russians brushed aside the charge, claiming that to meet revenue targets they were being forced to pump more and more oil at a lower and lower prices, and thus were robbing themselves. They needed, “a commitment from OPEC not only to live within its production quotas but to lower those quotas, as well.”

A few weeks later, on Nov. 15, 2008, the Saudi-owned, very large crude carrier (VLCC), the Sirius Star, carrying two million barrels of crude oil bound for the United States, was hijacked 450 nautical miles off the coast of Kenya.

While thousands of ships of all kinds ply the waters of the Indian Ocean every year, the ability of Somalia-based pirates to find the VLCC, and to board and capture her, was not a small feat. “I am stunned by the range of it,” said the American Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Mike Mullen at a news conference. “The ship’s distance from the coast was the longest distance I’ve seen for any of these incidents.”

According to U.S. military sources, one does not just ‘find’ a ship hundreds of miles from shore. One needs ‘real time intelligence.’ Such an operation had to have had the help of a sophisticated nation state. Only two could have done the job: Russia or the United States.

Potential Actions

In anticipation of potential disruption of critical oil transportation, the U.S. may want to consider expanding its and its allies’ presence in the Pacific Ocean and Persian Gulf to assure freedom of navigation if threatened. This may include not only naval forces but also U.S. Air Force long-range aviation, both of which are critically important to keep sea passages open. Also necessary to consider, robust air, land and sea-based U.S. and allied missile defenses.

What is not often understood is that long-range aircraft play a vital role in countering an adversary’s ability to launch offensive aircraft and missiles. This factor alone calls for accelerated procurement of the F-35 stealth fighter and continued emphasis upon the Next Generation Air Dominance program. Patrolling these straits is an expensive proposition, and it means America’s allies, much more dependent on imported oil than the United States, will have to step up to help meet this challenge.

New Secretary ‘Gets It’

As Aaron Mehta writes in Defense News, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper understands exactly this threat and needed response. During his confirmation hearing, he called for “expanding base locations in the Pacific while continuing regular freedom of navigation operations in the region…”

Pat Cronin of the Hudson Institute echoes this point, explaining that the secretary is proposing “The…right to work on a more distributed set of access points throughout the Indo-Pacific in geographically strategic locations, where diplomatic and development support from the U.S. and allies and partners can ensure sustainable engagement to build capable partners and strengthen deterrence.” Singapore, the Philippines and Thailand are three key American allies on whose territory new military facilities could certainly be built.

Iranian rogue behavior in the Persian Gulf led to what President George W. Bush apparently thought of as the “mullah’s premium”— a $15 a barrel upcharge on oil due to Iranian interference in tanker traffic in the early part of this century. This added $300 million daily to America’s energy bill. That is almost exactly the surge in oil prices that has now happened due to the apparent Iranian or Iranian-instigated attacks in September.

America must be watchful of any hegemonic effort to interfere with the maritime flow of oil and its related on-land adjacent production and processing.

Peter Huessy is President of GeoStrategic Analysis, and a former senior defense consultant a the National Defense University.