The Biden administration published its National Security Strategy in mid-October. The document epitomizes what is wrong, intellectually, and strategically, with the current administration’s strategic perspective. Its greatest failure is the securitization of all topics with no attendant focus on any given strategic question. While the Biden administration faces a crisis across Eurasia that is close to drawing the U.S. into active warfare, it has engaged itself intellectually in a public-facing task with no actual substance. The National Defense Strategy, published shortly after the National Security Strategy, simply reinforces the former document’s follies.

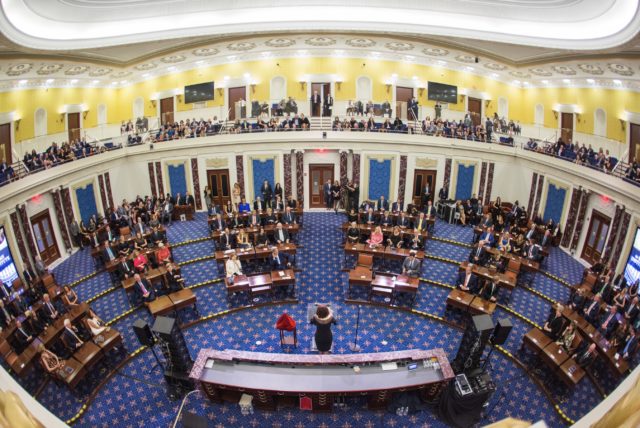

The Biden administration may be derelict in its duty to secure America’s defenses. However, Congress can act strategically, that is, compel the administration to accept a more coherent defense posture and advocate the capabilities and budgets the military actually requires. This would be well within the legislative branch’s constitutional role, and entirely apt given the current situation.

National Strategic Theater

Congress requires every administration to publish a National Security Strategy, but the document released by the administration is the apex of strategic bureaucratization. It is not a defense strategy, nor is it a grand strategy. It is, rather, a messaging exercise primarily for domestic audiences.

In one sense, the National Security Strategy, like many of its predecessor documents, says little about an administration’s actual policy. This document is jam-packed with priorities from countering China and Russia to mitigating climate change and ensuring American resilience.

Nevertheless, the structure of the Biden National Security Strategy does point to a strategic hermeneutic, a set of assumptions about the world, its major actors, and its critical dynamics that are useful to those who seek to understand policy. Four elements are relevant. All of them point to a lack of seriousness, and more fundamentally, to a lack of strategic change since the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

First, the National Security Strategy is an ideological manifesto, not a realistic look at, for lack of a better word, the security elements of Eurasian competition. It begins with the same rhetoric that has become commonplace in any administration’s national security strategy—the world is “more dangerous” than at any previous point, yet the United States retains an “enduring role,” with its strategy’s precepts remaining as sound as they were 10, 20, or 50 years ago. The notable aspect, however, is the explicit equivalence between traditional and nontraditional threats. The U.S. must compete and cooperate simultaneously. The climate disaster and public health questions, even inflation issues are worthy of consideration and relevant to a security assessment. Of course, there is an overlap between climate, inflation, health, and other questions and a nation’s broader strategy. But a security strategy is the wrong venue in which to discuss, for example, climate adaptation or an anti-inflationary policy. If every issue is a security issue, none is.

“Integrated Deterrence”

Second, the National Security Strategy demonstrates the degree to which the Biden administration does not see current Eurasian competition as military competition. The focus on “nontraditional security issues” dovetails with the Biden administration’s doctrine of “integrated deterrence.” The National Security Strategy defines it as “combining our strengths” to deter America’s adversaries. This concept looks much like “smart power,” the Obama administration’s doctrine that combined diplomacy and military action to achieve American interests—in other words statecraft. Much like smart power, integrated deterrence appears to be a meaningless term with no relevance to the national security professional or interested citizen. In reality, it is a strategic dog whistle to Biden’s political allies that the administration does not prioritize conventional deterrence and warfighting capacity. Integrated deterrence serves to create justifications to cut and reorient defense spending and traditional military means in favor of domestic policy priorities.

This points to the third issue, the Biden administration’s supposed conviction that American economic resilience is the foundation of national power. In the abstract this claim is undeniable: Economic power is the wellspring of military strength. Yet it is no longer 1945 or 1960. The United States must apply its power with care and prudence. Instead, the Biden administration has dressed up climate handouts as an anti-inflationary measure. The lost art of Net Assessment—the art of strategy—can be understood as compelling or inducing an opponent to take steps in one’s own interest. The Biden administration has triggered and sustained an inflationary crisis and concurrently introduced a defense strategy that will hollow out U.S. military capacity. The administration’s point is to justify reducing American military strength because it sees competition as a complex concatenation of diverse causes.

Fourth, the administration’s refusal to recognize Iran as a legitimate strategic threat reveals its unwillingness to recognize tangible competition and adapt to new circumstances. The Biden team still clings to the chimerical Obama-era dream of a regional realignment, in which Israel and Saudi Arabia were humbled, and Iran elevated. The U.S. recently bullied Israel into conceding its maritime space to Hezbollah, and by extension to Iran. “Regional integration” empowers Iran at the expense of Israel and the Gulf Arabs. All this while Iran provides Russia with weapons to strike targets throughout Ukraine. Although the new Iran nuclear deal may be dead for now as protests surge in the self-styled Islamic Republic, it will return when the news media conditions have shifted.

National Defense Strategy

The National Defense Strategy simply doubles down on the National Security Strategy’s mistakes. Indeed, it offers slightly greater clarity as to the military meaning of Integrated Deterrence. The military has five tasks, the first two of which, protect critical infrastructure and prevent a nuclear strike on the U.S. homeland, have either very little to do with the military, or very little to do with the current strategic balance – despite bluff and bluster, China and Russia are not on the cusp of attacking the U.S. with nuclear weapons. Third on the priorities list is what was termed, in an earlier age, conventional deterrence, the ability to prevent adversaries from actually acting decisively to modify the strategic balance by capturing key territories.

In turn, the Defense Department will emphasize “campaigning,” a concept that essentially reduces to “conducting daily actions with a vague strategic purpose in peacetime.” Why the word “campaigning?” To convince the casual reader that the Defense Department is engaged in a robust competition and knows it and avoid the obvious reality that the United States is completely unready for a major conflict.

Congress and Defense Policy

A more sensible National Security Strategy would have begun with a recognition of the current geopolitical situation: the struggle for Eurasian mastery that involves the U.S., China, Russia, Iran, and the various secondary powers throughout the landmass. American strategy has a singular objective, to preserve the extant Eurasian security system and counter Chinese, Russian, and Iranian attempts to overturn it. This requires all elements of national power, but most specifically military. America’s adversaries pose a military threat and seek to achieve their goals by military means.

The Biden administration does face a dangerous world. Russia makes nuclear threats. The war in Ukraine drags on. Russia spoils the global food and energy supply. China pressures Taiwan. Xi Jinping is installed as Maximum Leader. Iranian weapons supply Russian forces, and Chinese technology likely assists their development.

The Biden administration’s diffuse and domestically focused response is inadequate and dangerous.

The advantage of the federal system, with its separation of powers, is that it provides multiple avenues of policy oversight. Only the executive branch can fight a war. Modern Americans have forgotten that the very purpose of the presidency, with its sweeping powers, unitary nature, and dictatorial character, was to allow it to act with dispatch and secrecy. Hence the president has broad latitude in matters of statecraft, that is, when he employs military force or diplomatic elements to further American interests.

This latitude is not sacrosanct, however, when one shifts to long-term discussions of strategy or force structure. It is Congress that approves the budgets for the military, and Congress that scrutinizes and holds to account American generals and admirals during wartime. The legislature has a constitutional right to impose its strategic concepts upon the executive so long as individual senators and representatives are not directing military operations.

Congress has taken the lead in a constructive manner on military questions at previous points in U.S. history. Most notably, before the Second World War, Carl Vinson spearheaded the 1938 Naval Act, increasing Navy fighting strength by 20 percent, and then the 1940 Two-Ocean Navy Act, which kick-started American defense industrial production and provided the Navy with the fighting core it would need during the Pacific War.

In today’s context, there are five concrete steps that Congress can take to improve America’s ability to confront a major Eurasian military challenge.

Right-Size the Force

First, Congress can right-size the force. Expanding the services provides a strategic reserve of trained manpower. As the Russo-Ukrainian War demonstrates, modern combat remains brutal and casualties high. Ensuring that all Services meet their annual recruiting targets at minimum is a military necessity. Even more reasonable, however, would be to expand the Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force’s top-line personnel numbers to ensure that they can sustain damage and keep fighting. In turn, remaining restrictions on new recruits should be re-evaluated, particularly those that disqualify potential soldiers for “crimes” that are now legal.

Second, Congress can compartmentalize funding in toto for strategic reinvestment. It is not only the military services and Pentagon that will demand new funds. The Biden administration’s national strategies are, once again, veiled excuses to raid the defense budget. The executive, ventriloquizing the services and employing pressure from the Democratic Party’s left, will seek to siphon off as much cash as possible. Some of the endeavors the Biden administration proposes will be reasonable, particularly those that ensure the U.S. has access to specific sovereign capabilities, like semiconductor fabrication facilities, that it can employ during a major conflict. Yet the competition America faces requires a significantly enlarged defense budget, something around at least seven percent of GDP instead of the current approximately three percent.

Strategy

Third, Congress can provide the services with the support they need to think about strategy. The services, barring arguably the Marines, are listless, with little understanding of their role in modern combat. Contrary to the still-fashionable demands of Jointness, it is far more intellectually reasonable to begin with the services. Strategic thought requires new blood – this will be found far from the Joint Staff and standard military-operational structures, and particularly within the services themselves. Congress can oversee the revitalization of actual service strategic cultures. Of equal importance, Congress can expand those who participate in actual strategic thought, linking with think-tanks and academia far more effectively than today to ensure more comprehensive military thinking.

Fourth, Congress can revitalize the Defense Industrial Base. This demands far more than simplistic industrial strategies. Rather, it requires supporting smaller defense providers; incentivizing the development of dual-use technologies, particularly in unmanned contexts; reducing regulatory barriers for defense collaboration; and subsidizing various forms of training, particularly for large industrial production and repair of warships. Over time, automation will improve efficiency and displace human labor, but during the current Sino-American competition, manual labor and traditional productivity will remain crucial.

Fifth, Congress can properly fund two critical partly military capacities, a proper logistics system and a more robust space industry. The U.S. military lacks the sealift capacity to sustain itself in combat. Its sealift capabilities rest on a far broader foundation, however, than just military assets. The U.S. relies upon the Merchant Marine to conduct resupply missions during a major war. Much like America’s satellite system, the Merchant Marine is sufficient for peacetime, but not for wartime. Both require a funding injection and explicit government support.

Conclusion

Congress cannot make foreign policy wholesale. But it can, through prudent, aggressive action steer the ship of state on the course it ought to take. Congressional actions like those outlined above can push back against the Biden administration’s attempted erosion of traditional deterrence and military capacities, and ensure the United States is prepared for a Sino-American war.

Seth Cropsey, a former naval officer, is President of the Yorktown Institute. He previously served as Deputy Undersecretary of the Navy and acting Assistant Secretary of Defence for Special Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict.